March / April 2020

Milford Buchanan and the Shelburne Dory

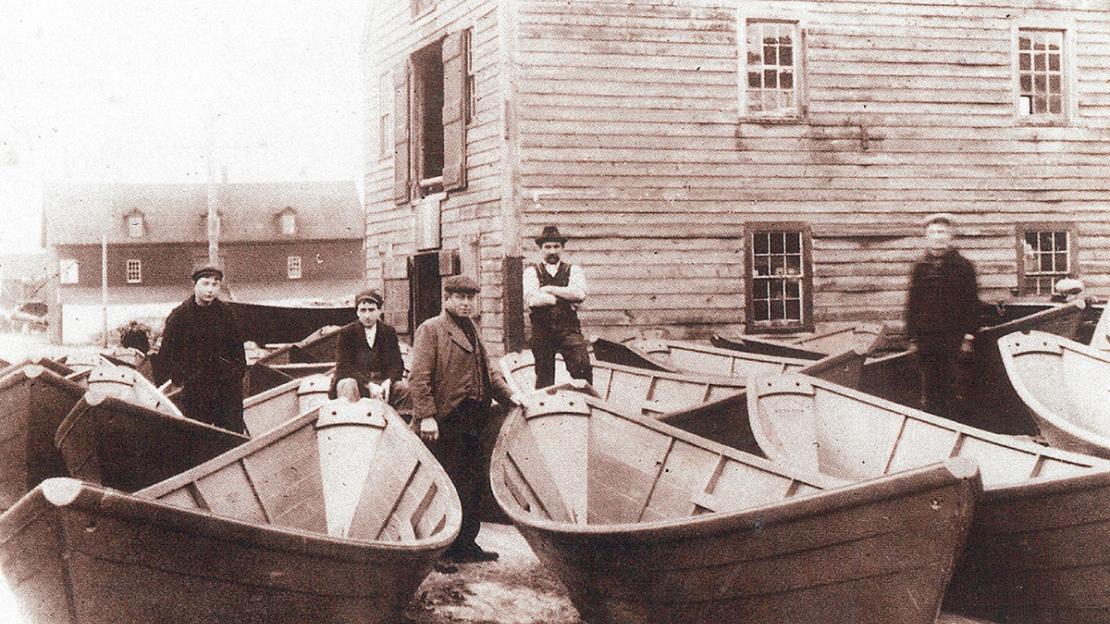

The seven-man crew at the J.C. Williams Dory Shop in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, shown here in about 1900, could send one to two dories per day out of the shop’s second-story doors during the height of the company’s production.

Milford Buchanan and I had already bent the pre-made bottom of the dory into the building jig—or horse, as he called the ancient cradle on the boatshop floor at the Dory Shop Museum in Shelburne, Nova Scotia. We had wedged the flat bottom tightly in place using posts and jacks that had been used to spring more than 50,000 bottoms to the standard 31⁄2" rocker. All five frames and even the stem and the transom were attached to the bottom before we bent it into place.

Now, I grabbed a spirit level and held it vertically alongside the stem to check it for plumbness. Buchanan looked at me and said, “I guess you could do it that way.” He took the level and set it on the workbench, then walked to the end of the shop and shut one of the bay doors. He returned to the boat. “See that stick on the edge of the door? Sidney Mahaney put that there. That’s plumb.” Mahaney had started building dories in this same building as a teenager, in 1914. Straddling the dory and squinting with one eye, Buchanan directed me to nudge the stem so that it would be plumb before securing braces to hold it there. That’s how it’s always been done here, where Buchanan, a fourth-generation boatbuilder, has carried on the tradition as the museum’s lead builder since 2003.

Shelburne exploded into existence in 1783 with the arrival of about 10,000 British Loyalists fleeing from the newly independent United States of America. They’d sided with the losing team and, no longer feeling welcome in the new republic, sought a friendlier territory that was still under British rule. A well-protected, deep-water harbor seemed to make Shelburne ideal for resettlement, and within a year its population reached 17,000, making it the fourth-largest city in North America. But it subsided just as fast after it became clear that farming the area’s spare, rocky soil couldn’t support the city’s population. Most of the loyalists moved on, and the population fell to less than 1,000. One among those who stayed was a German former militiaman named Conrad Bohannan, who anglicized his family name to Buchanan.

To read the rest of this article:

Click the button below to log into your Digital Issue Access account.

No digital access? Subscribe or upgrade to a WoodenBoat Digital Subscription and finish reading this article as well as every article we have published for the past 50-years.

ACCESS TO EXPERIENCE

2-for-1 Print & Digital Subscription Offer

For this holiday season, WoodenBoat is offering our best buy one, get one deal ever. Subscribe with a print & digital subscription for $42.95, and we’ll give you a FREE GIFT SUBSCRIPTION to share with someone special.

1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION (6 ISSUES)

PLUS ACCESS TO MORE THAN 300 DIGITAL BACK ISSUES

PRINT+DIGITAL $42.95

Subscribe

To read articles from previous issues, you can purchase the issue at The WoodenBoat Store link below.

Purchase this issue from

Purchase this issue from