The Magic of MERLIN

Resurrecting a family’s legacy

Resurrecting a family’s legacy

KRAIG CARLSTROM

After her restoration, the immaculate gaff cutter MERLIN, at 85 years old, sails on a cloudless autumn morning on Port Phillip Bay in Melbourne, Australia.

Like seductive sirens, certain beautiful vessels invariably attract the roving eye of a sailor. Through their sensuous sheerlines, the balanced symmetry in their curving bows and counter sterns, and the elegant proportions of their rigs, they sing the kind of alluring songs that cause old salts to glow in remembrance of times long past, when youth overwhelmed cold common sense and we surrendered to their irresistible charms. MERLIN, a lovely little teak-built British cutter, is just such a yacht. At the Australian Wooden Boat Festival in Hobart, Tasmania, more than 500 gleaming boats and launches lay before me under a cloud of dazzling, multicolored bunting, and yet MERLIN was the one whose siren call most enchanted me.

HUGH COUNSELL

In 2008, the Counsell family tracked down MERLIN to a rural Queensland back yard, where she was deteriorating in the harsh climate.

She is certainly well-named, for Merlin was the ancient wizard of the Britain of Arthurian legend, a Druidic sage and shape-shifter, and the weaver of spells who created the magic of Camelot. I could see at once that like her namesake this cutter was a boat with a commanding presence. She has character, personality, and the kind of lovely, mellow patina that comes only after long experience of deep-sea voyaging. MERLIN is that rarity, a classic English hard-weather cruiser from the 1930s, a tough little survivor that has twice made safe global circumnavigations and logged innumerable sea miles over the course of her 85 years afloat.

MERLIN made many adventurous ocean voyages under the ownership of an English yachtsman, Lord Stanley of Alderley, who bought her in the spring of 1937. In the book he wrote about his experiences, Sea Peace, he devoted two chapters to MERLIN and described her as “the finest ship I ever owned.” His lordship had 12 yachts in his 35 years under sail, but MERLIN was undoubtedly his favorite. He and a paid hand named Parsons took her out in “the most beastly weather” and were unstinting in their praise for her stout seakeeping capabilities. In 1934, Lord Stanley had watched her being built to Lloyd’s 18A classification by the top-notch craftsmen at the Philip and Son shipyard at Dartmouth in Devon. He therefore knew that nothing but the finest materials had gone into her construction: the best Burma teak in her planking and deck, English oak in her keel and in her grown double-sawn frames, teak and oak in her saloon, and high-grade naval brass in her fittings. Designed for G.S. Burge by A. Letcher of Capt. O.M. Watts, the London ship’s chandler, she was 36′6″ LOA, 29′3″ LWL, 9′6″ beam, and 6′1″ draft. She displaced 11 tons and carried a 700-sq-ft Bermudan rig on Sitka-spruce spars.

In the 1960s, flying the burgee of Britain’s Royal Cruising Club and under the command of its commodore, Dr. R.A. “Ronnie” Andrews, MERLIN continued to log impressive transatlantic passages, voyages to Norway and Spain, a circumnavigation of the British Isles, and a circumnavigation of the globe. Through all the foul weather she encountered, MERLIN was never knocked down and never disabled by a sea. Her design may have sacrificed some speed to seakindliness, but as Andrews put it nicely: “Praise the Lord for a stiff boat.” Andrews’s discerning wife, Rosemary, an artist, described her as “a swan among geese.”

KRAIG CARLSTROM

Twelve years after finding MERLIN, and saving her for a second time, John and Rosalie Counsell, with their eldest son, Hugh, relax in the cockpit and savor the results of the meticulous restoration that Hugh led.

In the late ’70s, MERLIN vanished into the tropical backwaters of northern Australia, a place where intense and unrelenting heat, humidity, and torrential rains invariably sound the death knell for old wooden boats. There, she spent years going nowhere. Due to the drawn-out and debilitating illness of her owner, who had her for more than 20 years, she ultimately endured the unspeakable ignominy of being hauled far from saltwater and left unprotected in a semirural back yard. But then, in what can best be described as a miracle of obsessive perseverance, the family of Dr. John Counsell, who with his wife, Rosalie, bought the boat in 1975 in England and sailed her all the way to Australia, tracked down the yacht. They were flabbergasted when they eventually laid eyes upon the blistered, sun-bleached hull, tilted bow-down and half-full of rainwater with a “festival of fungus” consuming the charts and pilot books that had once helped to guide her safely from the far side of the world.

Even so, John, a cardiologist and a lifelong dinghy sailor, sensed that there were still signs of life in MERLIN. Her heavy Moulmein teak planking from Burma was still tight, and despite all she had endured, the timeless elegance of her hull shape remained intact. In 1977, at the end of their two-year voyage from Britain, John and Rosalie had sold MERLIN to focus on profession and family—but now, surveying the parlous state of his old boat, John couldn’t bring himself to abandon her in what was clearly her hour of greatest need. Between clenched teeth he told his eldest son, Hugh, “We can’t leave her here.”

The then-owners, an elderly couple, were eager to see the boat saved, and John reacquired her for a nominal amount and agreed to take on the project. He had her trucked 1,500 miles south to a large shed on their home farm in the foothills of Victoria’s Dandenong Ranges. There he subsequently spent a considerable sum on a meticulous five-year professional restoration, completed in 2018.

And thus, I found myself in Hobart, arrested at the water’s edge by the sight of this gorgeous old vessel. Standing, beaming on the dock next to his father’s beloved boat, was Hugh, now 40 years old. It was he who became the persistent, obsessive dreamer who relentlessly pursued MERLIN and eventually found her in Queensland. Hugh and his twin sister, Claire, enjoy the delightful distinction of having been conceived aboard MERLIN during the long, meandering transpacific passage in which their parents logged almost 17,000 nautical miles, sailing slowly from Plymouth, England, to Melbourne, Australia, via the Panama Canal.

John, now 75 and blissfully barefoot on the teak foredeck, was coiling down lines after MERLIN’s hazardous 435-mile passage across Bass Strait from Williamstown. Father and son share a profound passion for wooden boats, and they regard MERLIN with the deep affection that close-knit families traditionally reserve for their revered elders. It was an honor to be invited aboard, and I turned to Hugh for the details of his family’s extraordinary life-changing experiences with the magic of MERLIN.

HUGH COUNSELL

Above left—Extensive rot in MERLIN’s deckbeams and sheer clamps, plus nail sickness in her sawn oak frames, meant that each piece had to be carefully replaced without compromising the shape of the hull. The lodging knee visible here shows the extent of the deterioration in her wrought iron, which was originally used for lodging knees and floors. Above middle—Cast bronze lodging knees replaced those of wrought iron, which is now unavailable. Above right—A full complement of new bronze floors had to be fabricated.

As a boy, Hugh became intimately familiar with his parents’ many stories about MERLIN. They created in his mind’s eye the perfect, romantic image of the ideal cruising yacht. “MERLIN captured my attention at a very early age,” Hugh said. “She was, in a sense, my very own Boy’s Own Annual adventure story,” he said, referring to the newspaper published in Britain for young readers from 1879 to 1967. “I was smitten by the beauty of her lines.” The family home displayed large, framed photos of MERLIN, and his father’s study contained a library of sea books, including nine photo albums full of pictures capturing every aspect of her voyage from Britain to Australia.

HUGH COUNSELL

The teak coach roof was suspended above the hull while the correct camber for new deckbeams was calculated. Until they could be installed, together with new beam shelves and stringers, a temporary plywood beam shelf secured the hull’s shape.

MERLIN was everywhere and yet nowhere, for Hugh’s parents had sold her in order to focus all their attention on providing for their growing family. Years later, his search for MERLIN would build into something of an obsession. In 2008, at a time when he was contemplating building or buying a boat capable of world cruising and was searching through the secondhand-yacht listings, he became aware of subconsciously looking for MERLIN. “She was my ideal,” he said, “the perfect vessel, the boat that ticked all the boxes. I knew I would never, ever find a boat like that in Australia, but I thought I might be able to find one like her in the U.K. and sail her back to Australia, just like mum and dad. I found a nice 40′ cutter in England, but when I contacted the broker he laughed and told me, ‘Mate, if I had five boats like that I could sell them in the blink of an eye.’”

But then Hugh began to think seriously about MERLIN and realized that she could still be in Australia. “I was searching online,” he said, “when I discovered MERLIN has a sistership in the United States in AIMÉE LÉONE [see WB No. 204]. Her owner, Terry Rhoads, had posted some details on the WoodenBoat Forum [forum.woodenboat.com]. I emailed Terry, and he sent me a very grainy mobile-phone image that showed MERLIN under covers on a hardstand looking very sorry for herself. He thought she was somewhere near Brisbane, so I started calling brokers and marine surveyors in Queensland. I made half a dozen calls before one surveyor advised me to call a marina at Caboolture on the north side of Moreton Bay. ‘That,’ he added ominously, ‘is where old wooden boats go to die.’”

HUGH COUNSELL

MERLIN was given a new coach roof and new deckbeams and sheerstrakes. Her original laid teak deck leaked badly and was beyond salvation. The composite replacement, solid teak planking over epoxied plywood, does not leak and also has greatly strengthened and stiffened the structure.

The marina manager confirmed that MERLIN had indeed spent many years there but that she had been trucked out 18 months earlier at the behest of the owner’s son when his father had become seriously ill. Hugh contacted the owners and explained his interest in finding MERLIN. He was invited to come and see her for himself. “Dad was a bit taken aback,” Hugh said. “He knew I had been looking for MERLIN, but never in his wildest dreams did he ever imagine I would successfully track her down. We flew up to Brisbane, hired a car, and drove out to meet the owners. We followed them out into the countryside, where we found MERLIN out in the open with no covers. Her hatches were off. She was sitting forward on chocks, a complete and utter mess. My initial reaction was a mixture of shock and disbelief. Suddenly, the beautiful visions, the romantic dreams from my childhood, were turning into the worst possible nightmare. Someone had started to use a belt sander on the starboard topsides but had given up after sanding a solitary patch, 3′× 3′. The would-be restorer was also responsible for drilling ten 1½″ holes in the hull, ostensibly to help drain the rainwater out of MERLIN’s bilges. “She wasn’t quite a Swiss cheese,” John recalled, “but it was close.”

The original, solid Sitka-spruce boom, with its bronze roller-reefing system, was found wrapped in the mainsail and lying under the boat. The mast, with all its fittings removed, was lying uncovered on the ground. The weather side, exposed to the westering sun, had deep checks and had been “absolutely beaten-up by the tropical weather,” Hugh said.

“The crazy thing about this,” he said, “was that in many respects the boat looked exactly as it did in our old family photos. Very little had changed. In fact, her old Beaufort life raft was still sitting on the coach roof, and when we went below we found life jackets and wet-weather gear that mum and dad had worn, still hanging on the pegs. Her CQR anchor was lying below with piles of their lines. The bookcase was still full of dad’s pilot books, and the chart table was crammed with all the old charts that dad had sold with the boat. Unfortunately, all that had ended up underwater, so it had become one solid mess covered by fungus. Dad was devastated. He was swearing under his breath. He felt really frustrated and annoyed that he had brought this lovely boat all the way out to Australia to finish up like this.”

But Hugh was looking at MERLIN through different eyes. “Despite her terrible condition, any damage appeared superficial, and the essentials were unchanged. I could still recognize the boat that mum and dad had stepped ashore from all those years ago. I was so glad that she hadn’t received a 1970s, 1980s makeover. There was no sign of any plastic. Down below, she was all teak. She had been preserved in a kind of time warp. I thought, ‘This is the ultimate barn-find! We could do something here.’”

HUGH COUNSELL (left), KRAIG CARLSTROM (right)

Above left—Two of MERLIN’s new Pacific jarrah deckbeams were fitted with graving pieces taken from the original English oak ones so that her carved official ratings could be saved. The rating shown here refers to the area deducted from her official registered tonnage. Above right—The carving showing MERLIN’s full registered tonnage and her hull number was also saved.

However, the Counsells did not have to look hard to see MERLIN’s structural problems. Hugh ran through the litany of decay: “The deck was rotting out, the deckbeams were all gone, there was rot in the sheerstrake, rot in the bulwarks. Wherever there was standing deck water, there was some rot. But overall,” he said, “the teak hull was still in good condition. Below the waterline, the hull was still tight and hadn’t opened up at all. There was no cracking in any of the topsides planks. The oak keel and the deadwood still looked pretty good.

HUGH COUNSELL

With her hull reconstruction completed, the focus shifted to rebuilding the interior, using original material wherever possible. Here, the galley structure starts to come together.

“On the flight home, dad and I were both wearing our rose-tinted spectacles. We figured the boat was probably going to cost around $120,000 or perhaps $150,000 to fix up [about U.S. $85,000 to $107,000], so dad decided they could manage that. We didn’t know, at that stage, how much the complete restoration would cost or how long it would take. All we knew was that we had to save her.”

The Counsells discussed a two-year commitment involving Hugh and one professional wooden boat builder. Hugh ended up mothballing his sound-studio business in Melbourne and devoting himself full-time to MERLIN’s restoration. “I did it because I love the boat,” he said. “I saw it as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, a project I could just throw myself into.”

John and Hugh flew back to Queensland, hired a station wagon, and filled it with every piece of MERLIN’s equipment they could find. “We were afraid that once word got out that the boat had been sold,” Hugh said, “she might be set upon by souvenir hunters. But, as we soon found out, that had pretty much already happened. While we were hard at work stripping the boat, we were astonished when several people came to us rather sheepishly bearing gifts. These were the fittings they had taken off her over the years. One couple had purloined the lovely old gimbaled brass oil lamps from the saloon and had them as nautical decorations in their house. Someone else came up with the original bronze running lights and the navigation lights, which were all brass oil-burning lamps. Someone else came with the nicely carved nameboards, which had been fixed either side of the coach house. It was awesome.”

Hugh spent six months stripping the boat bare inside and out, preparing the shed for the restoration and getting the right tools to make the whole operation as efficient as possible. “I felt a deep personal responsibility to do this restoration right,” he said. “Everything I took off the boat was meticulously labeled and catalogued in my laptop, because in the early stages I just did not know how long the restoration was likely to take. It turned out to be five long years before we were able to put all the bits and pieces back again, so it was just as well that I had clearly labeled everything.” But by the time he had taken everything out of the boat, Hugh realized that he faced a much bigger job than he had ever imagined and that there was no way he was going to be able to do the work alone. He needed professional help and settled on the very experienced team at F.J. Darley Traditional Shipwrights of Williamstown. Ferdi Darley had four of his best men working on MERLIN in stages over the ensuing five years. One of them in particular, Justin van Abel, made a most significant contribution with the exceptional quality of his craftsmanship.

The guiding principle in the restoration was to make MERLIN as strong, if not stronger, than she was when Philip and Son built her in 1934. “Our aim was to keep her going for another hundred years,” Hugh said. “I didn’t want to be coming back and doing it again. At the same time, I didn’t want to build a new boat. We felt it was important to retain as much of the original fabric of the vessel as we could. At the end of all our work, I didn’t want to be looking at a new boat. I wanted to be looking at an old boat in fantastic condition.”

HUGH COUNSELL

MERLIN’s 38-hp, three-cylinder Yanmar 3JH5E diesel engine, which sits on soft mounts under the companionway, gives the easily driven hull a comfortable cruising speed of 6 knots at 1,800 rpm. The original engine was a 10-hp, two-cylinder Petter diesel.

MERLIN originally had 38 pairs of double-sawn frames made of English oak and set on 12" centers, with each frame assembled from two or three separate grown futtocks held in place with iron clench nails, which was common practice among British boatbuilders in the 1930s. English oak (Quercus robur) is, however, particularly susceptible to nail sickness: Radiating out from each of MERLIN’s iron fastenings was an area showing its telltale signs of blackened decay, almost like charcoal. This was where the first significant structural issue arose.

Of her original frames, all but one on the port bow and six in the stern were replaced with laminated hardwood ones. The builders started in the ’midship sections, working first forward as far as the maststep and then aft, replacing every third frame one at a time. They first carefully cut out a frame using a reciprocating saw and then replaced it right away with a laminated one to ensure that no hull shape would be lost. In the beginning, when they felt it was important to retain as much of the original timber as possible, they simply cut out the parts of the frames affected by nail sickness and scarfed in new timber. But they had no sooner started down that road than they realized there was just too much to be replaced. The whole boat needed to be reframed.

“We left the stringer and the beam shelf intact,” Hugh said, “and used those to wedge off when we inserted the laminated frames. The frame dimensions varied, but around the maststep they are around 150mm wide [about 6″] while others were 80 or 90mm [about 3″ to 3½″]. We were initially hoping to replace the English oak frames with sawn frames like the originals, but the timber we sourced, a gray gum (Eucalyptus punctata) from Victorian forests near Orbost, was gum-veined and not clear, and I didn’t like it much at all. We found that within 24 hours, the frames had moved so much that they no longer fitted. That’s when we decided to switch to laminated frames. The timber we finished up using is marketed as Pacific jarrah and is, in fact, a tropical South American hardwood (Manilkara bidendata.) It’s very dense, clear-grained, and extremely heavy—over 1,000 kilos per cubic meter [about 62.4 lbs per cubic foot], so it sinks. But it is also exceptionally strong and very durable. Having seen so much rot, the key characteristic for me was its durability.”

KRAIG CARLSTROM

MERLIN has miraculously retained all her original bronze fittings.

MERLIN’s 1⅛″-thick teak hull planking was in perfect condition other than the sheerstrakes, which had suffered from rot as fresh water worked its way down through the bulwarks and their joints with the covering boards. “Once we reframed the whole boat,” Hugh said, “it was just a case of popping each individual plank off.” During the reframing work, they had driven temporary screws through the planking and into the new frames, with plywood pads to cinch them firmly in place. This had helped hold the hull’s shape as the reframing work continued. Then it was time to recondition the planking. “We removed one plank at a time, cleaned it up, primed it, and stuck it back on,” this time with the permanent fastenings, ¼″ copper rivets. “In doing so, we found that when MERLIN was built in 1934, the shipwrights at Philip and Son did not prime the inboard faces of the planks. It was simply left as bare teak.”

Hugh pointed out that some of the original ways of doing things were not necessarily always the best ways. MERLIN’s ¾″-thick, 2″-wide, and 1′-long wrought-iron strap floors were, he said, a good example of that. “Many of the floors had lasted incredibly well,” he said, “but many others had completely rusted through. They needed to be replaced. I did try to find the high-quality iron I needed, but it’s just not available these days. So we went one better and replaced the floors with bronze—an alternative that should have been available when the boat was built. We removed all the old floors, had them sandblasted, then filled all the divots with a mixture of polyester resin and talcum powder and cleaned them up to serve as patterns for casting. We did briefly consider replacing the floors with hardwood [the method used on AIMÉE LÉONE], but since all our tanks are down in the bilge, we had to retain all the available space, so we went with bronze floors.”

MERLIN’s original laid teak deck, with planks 2½″ wide and 1⅛″ thick, had been worn down to a thickness of less than ¾″ in places, especially around the scuppers. The teak had been blind-fastened to the 2″ × 2½″ oak deckbeams. The entire deck had to be replaced. “The decision to go for a composite replacement deck was dad’s idea,” Hugh said. “His reasons were first and foremost based on the benefits of the bracing effect, the significant increase in lateral strength, and the stiffness that this construction technique would give the boat. I was trying to keep the boat as traditional as possible. I had heard so many horror stories about people who had gone that way and subsequently discovered rot in the plywood substrate. It’s such a pain to repair, whereas it’s relatively easy to repair a planked deck finished with the traditionally cotton-caulked and payed seams. What I didn’t want was a repeat of the incessant deck leaking that had so often made the lives of Ronnie Andrews and his crew a misery during their circumnavigation. Apparently the deck leaks were so severe that Ronnie is said to have slept ‘all-standing’ in his oilskins and sea-boots.”

HUGH COUNSELL

MERLIN returns to her proper element after decades of neglect and five years of exacting restoration.

The issue was eventually decided not so much by the need to stop annoying leaks but by a breathtaking realization that an inordinate amount of precious rainforest teak would have been wasted in machining planks to the required size. Knowing that teak is such a prized and scarce resource, Hugh was not prepared to waste so much of it as sawdust in order to satisfy some traditional aesthetic. “It was a crazy, expensive, and almost criminal amount of wastage,” Hugh said, “so I was not prepared to do it. We then had to look at the best possible way to build a composite deck that looked exactly like the original.” The solution was to use plywood sheathed in fiberglass cloth set in epoxy followed by an overlay of teak planks.

Using routers, the underside of the ½″ plywood was grooved to simulate the look of the original teak planking from below. After it was installed and the fiberglass sheathing completed, the deck was topped with sprung teak planks 19/32″ thick and 2½″ wide glued down with purpose-formulated epoxy from Teak Decking Systems. Temporary screws with plywood pads were used here, too, this time to hold the planking down securely until the glue set, with the screws set in the seams to avoid marring the teak. (After the screws were withdrawn, the holes they left were also filled with epoxy.) The planks were nibbed into two quite wide kingplanks on either side of a centerline seam. All the seams were filled with Teak Decking Systems caulking.

Margin boards of 6″-wide iroko were lap-joined to the plywood. “That gave us solid timber out to the edge,” Hugh said, “where so many of the fittings were fastened and a really strong, watertight joint that was finished in teak.”

KRAIG CARLSTROM

Thanks to the Counsell family, MERLIN, the veteran voyager, retains the rare, timeless quality of a lovely historic vessel again made worthy of the sea.

KRAIG CARLSTROM

With restored trunk cabin sides and her new deck emulating her original one, MERLIN conjures a memorable era of British yachting—on deck as much as below.

After a good deal of agonizing, Hugh decided to go along with Darley’s professional recommendation to spline MERLIN’s topside planking seams to assure a smooth, low-maintenance, and long-lasting finish.

With the restoration completed, MERLIN has taken her rightful place among the classic cruising yachts of the modern era, and the family intends to continue cruising her at home, in New Zealand, and in Tasmanian waters.

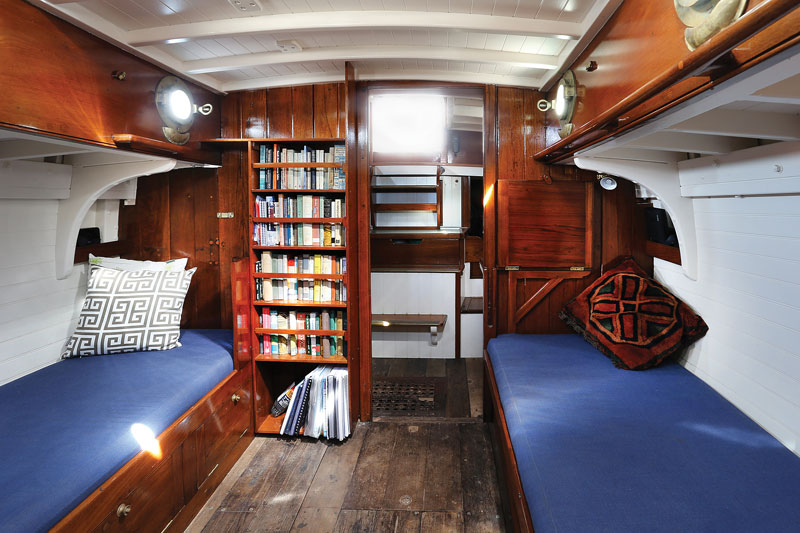

One of the many truly miraculous things about MERLIN, and the aspect that was most endearing to me, is the fact that she remains an almost perfect time capsule of the staunchly spartan 1930s, a time when doughty British coastal cruising yachts were expected to put to sea with only the barest necessities for crew comfort: a small hand-cranked porcelain head in the forepeak, a couple of narrow canvas-covered bunks amidships, a simple little galley sink with a cold-water pump, and perhaps a small paraffin cooker—but no more. With the best of British phlegm, one was expected to take one’s shower briskly on deck beneath a bucket of inevitably chilly salt water. Under Lord Stanley’s ownership, MERLIN’s one and only concession to heavy-weather cruising comfort was the crude charcoal-burning heater he lashed to the base of her mast. Thanks to the aesthetic sensitivity of the Counsell family, MERLIN remains gloriously original, and that, I think, is one of the family’s most significant accomplishments with this project.

It was a genuine pleasure to go below with Hugh, sit quietly on the well-worn canvas-covered bunks in her cozy saloon, with her round brass ports flung open to allow a cool sea breeze to waft through the space. The small dropleaf table had been neatly stowed out of sight beneath the bare teak sole while old brass oil lamps cast a warm golden glow over her mellow teak interior. It was a timeless scene, one familiar to voyagers down the ages. And thanks to the family’s unstinting efforts, it is a scene that will be savored long into the future.

Bruce Stannard is a regular contributor to WoodenBoat.

Down below: A time capsule of a simpler age

KRAIG CARLSTROM

Forward of the saloon, there is an enclosed berth to starboard and lockers to port, and the head is discreetly hidden in the forepeak behind a paneled teak door.

KRAIG CARLSTROM

A bulkhead separates the navigation station and galley from the generous, but simple, main saloon. The Counsells’ restoration closely followed the original interior configuration.

KRAIG CARLSTROM

The navigation station, now neat as a pin, was once what Hugh Counsell called a “festival of fungus”.

KRAIG CARLSTROM

MERLIN’s elegant, light, and airy saloon glows with varnished teak, original brass fittings, and a handsome sea library. A dropleaf table stows below the cabin sole. The saloon has 6′2″ of standing headroom.

KRAIG CARLSTROM

A white-enameled, wrought-iron accommodation ladder (seen here looking aft from the head in the forepeak) provides access below from the offset foredeck hatch. Foulweather gear is stowed in a hanging locker behind the ladder, and four teak pigeonhole lockers provide adequate space for crew clothing. The original bare teak floor grating conceals a spare-chain locker in the bilge. Rectangular and circular glass deck prisms admit plenty of soft natural light below.

KRAIG CARLSTROM

The galley, to starboard opposite the navigation station, has an icebox, sink, and a small alcohol stove replacing the original paraffin stove.