The Spidsgatter PAX

Restoring a 1936 Danish double-ender—and reconstructing her history

Restoring a 1936 Danish double-ender—and reconstructing her history

COURTESY OF ROBERT GARRISON

PAX maneuvers through the fleet at the 2014 Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival’s concluding “sail-by,” with author Kaci Cronkhite at the helm. Among her crew was Merete Lehmann (in the yellow windbreaker) of Denmark, daughter of the spidsgatter’s 1938–1946 owner.

Despite many years of ocean voyaging, including a circumnavigation, I had never owned a boat of my own until 2007. On a blustery August day that year, a buxom 28' spidsgatter stole my heart. With 5′4″ of headroom, she was just my size. “Am I crazy?” I whispered to myself as a photo of her started appearing on the computer screen on my desk in Port Townsend, Washington. “But she’s perfect,” I argued in reply. The boat, PAX, had been in the region for 20 years, but no one knew her. Was she Scandinavian? Who built her? Who designed her? How had she come to North America? No one knew.

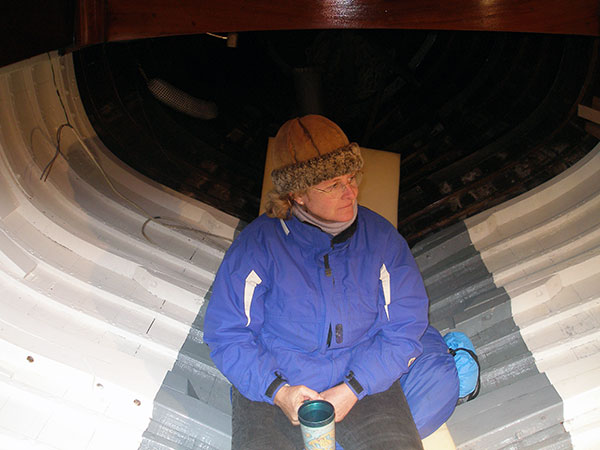

JAN DAVIS

Like many wooden boat owners, the author kept expenses down by doing as much of the restoration work as she could on her own, taking advantage of the fact that Port Townsend’s Boat Haven facility permits maintenance by owners.

I arranged to see the boat at the Royal Victoria Yacht Club in British Columbia. On her mooring, PAX was as stunning as in the pictures. But as the owner brought her toward the dock, my heart sank. Premonitions flashed before me like still frames of a movie. My hand shook a little. She was 71. I was 46. She was a classic. Even though I had managed the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival for years, I was a wooden boat novice.

When I stepped aboard, she barely moved. To me, double-enders have the shape of safety, the feel of home. My heart quickened. The sails, deck gear, and rigging were tired, and the interior was sparse but functional. I listened as the owner described the new fir mast he’d built, last week’s sail up to the Queen Charlotte Islands, his mock-up for a new cockpit. The heady scent of fresh varnish filled the cabin.

A colleague who had come along to offer advice lifted the floorboards and pointed at a weepy seam. From the rail, he pointed out a corresponding weathered copper patch at the waterline, like a 6″ × 3″ Band-Aid. “Probably need to replace a plank or two,” he said. I nodded but stayed focused on PAX’s motion; how stiff she remained as the two of us leaned outboard. “That’s doable,” I said.

The day being dead calm, we took PAX for a sea trial under power, leaving a wake etched like a bridal-veil train on a glass stage. She shouldered through a ship’s wake, solid as the quarter horses I’d grown up on in Oklahoma. I saw no red flags. With the festival three weeks away, I didn’t take the time for a formal survey.

I bought her.

In Port Townsend 10 days later, PAX started taking on much more water. Afraid she might sink, I hastily arranged a haulout at the yard next to my office. Within the hour, local boatbuilders, boat owners, and curious tourists swarmed around her. Buyer’s remorse swept over me. It was my turn to feel like sinking. I struggled to stay positive while people poked, prodded, and voiced opinions. Too busy to listen well and completely overwhelmed, I set out chalk so people could make notes directly on the hull and left a clipboard near the boarding ladder for “comments and questions.”

JAN DAVIS

Diana Talley of Taku Marine, who efficiently managed PAX’s haulouts next to her boatshop in Boat Haven, was one of many professionals involved in the boat’s restoration.

In a festival demonstration, her copper patch was peeled off to reveal signs of trauma and rot. Shipwrights weighed in. I knew all of the prominent boats and the “regulars” among the 200 boats at the festival. But now, a boat of mine played a role: She helped not only me but also others to understand how a patch might cover something serious. Now, I was an owner, an exhibitor, taking in every compliment and conjecture, acknowledging every smiling face and shaking head. What seemed like a crazy percentage of the 30,000 people at the festival freely offered advice. Then they were gone. I was alone with a boat I had only just met and barely knew, trying to piece together a conclusion about the way forward.

Deepening Relationships

I had known many Port Townsend boatbuilders and marine trades professionals over the years, but now I was a client. The first round of invoices arrived. Shocked and starting to panic at the lengthening list of projects, I begged my lead shipwright, Diana Talley—a woman of 25 years’ experience—for ways to keep costs down.

“Remove the ceiling,” she advised, as we stood alongside the hull. Wild-eyed, I shouted at her in frustration. “There’s nothing wrong with the ceiling! The project can’t get any bigger!” Calmly, she took my arm. “Come up top.” I followed her around the stern and up the ladder. Inside the cabin, she pointed down. “Those are the ceiling planks,” she said. I nearly fainted with relief. Another wooden boat term learned, and a task I could handle myself at a savings. For the next two days, that’s what I did.

KACI CRONKHITE

Eric “Moose” Wilson, a caulker and shipwright who worked on fish boats and workboats in Alaska, Washington, and Oregon, caulked seams on PAX in 2011, just a month before he died.

The relief was temporary. Removing the ceiling planking revealed her combination of sawn and steam-bent oak frames. Iron sickness was evident in one of the 22 sawn frames, a result of rusted fastenings and a less-than-perfect chainplate installation in the 1960s. With no permanent backstay, a jib, and a 51′-tall mast, 46′ of that above deck, those shroud and running backstay fittings carried a lot of load. Judging by the number of boltholes in the frames amidships, it was obvious that chainplates had always been an issue.

Farther aft, another sawn frame and five steam-bent ones were cracked. Ideally, all should come out and be replaced with European oak, matching the originals. Without a timely source for the big grown timbers and without a lot more money, that wasn’t possible. I weighed the options. What was essential? What could wait?

Sailors pressed me to get her sailing. Craftsmen pressed for craftsmanship. Preservationists pressed for a return to the original configuration. Ashamed of my ignorance, struggling with the weight of conflicting advice, dying at the costs, and feeling trapped, I longed just to sail away. But there was no escape. I wouldn’t let PAX die there, and I couldn’t give up. I drew up a short list of essentials at an affordable budget.

Above the waterline, one larch plank was replaced and five white oak frames were sistered. Three areas weakened by iron sickness were fitted with graving pieces—often called “dutchmen” but which my crew took to calling “dutchgirls.” Portions of two sawn frames were cut out and replaced with local black locust scarfed to what remained of the original white oak. Outside, the bottom was sanded to bare wood and soaked with boat sauce. Rusting fastenings were removed, their holes repaired so she could be refastened with bronze screws and bunged. Old caulking was reefed out of half the seams for recaulking. One month stretched to three. Finally, the hull was at least sound for use in inland waters. PAX took everything I had: my time, my pride, and all my savings. Was this the worst decision of my life?

KACI CRONKHITE

Amy “Shredder” Schaub, a 2007 graduate of the Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding, steam-bent white oak sister frames into PAX’s hull while serving as an apprentice with shipwright Diana Talley.

In February, six months after being hauled out, a rig-less PAX was lowered into the water, her interior bare, her cockpit empty. I was giddy. Friends and strangers came to watch. One brought a Susan B. Anthony $1 coin for luck, and others brought flowers, cards, sparkling cider, pizza. As PAX was lowered to the water, amid my tears, their faces leaned over the pier like angels in the sky above. Then, PAX floated—and only a little clear, cold salt water trickled in through her seams. A stream of water around the shaft stopped when I tightened the packing gland. The colleague who’d been with me the day I first saw PAX hopped aboard, handed extension cords to people on the dock, and flipped the ends of the two bilge pump discharge hoses over the side. Even so, friends were clapping, smiling, talking to each other. They weren’t afraid, and now, with PAX back in the water, neither was I.

For the next two days, I slept on the cabin sole. The pumps ran every 10 minutes, then every 20, then every hour as she took up. As I lay there in the bitter February cold, my spirit was restored. We’d done it. PAX had led me to new knowledge and a deeper appreciation of boatbuilders everywhere, and especially of Port Townsend’s marine trades community.

Origins

In those hours, I also thought about her original craftsmen. I studied PAX’s frames, traced the butt joints, admired the joinery. What hands first shaped those frames? Who spiled those planks? What was their community like?

The general view was that PAX was Danish-built, as were most spidsgatters. In 2009 I traveled to Denmark for the first time, determined to find PAX’s history. I searched archives at the Royal Danish Yacht Club, Copenhagen Amateur Sailing Club, and Sundby Sail Club, and city records in Kalundborg. I met spidsgatter sailors I’d corresponded with, among them Henrik Effersoe, a respected expert who took me sailing on his beautifully restored BEL AMI.

Spidsgatters in Denmark were built to class racing rules based on sail area, and Henrik owns a 38-square-meter boat designed by M.S.J. Hansen and built by Karl Thomsen of Kalundborg. He believed she was likely a cousin of PAX’s. He was as determined to find PAX’s origins as I was and arranged for me to go aboard other Hansen-designed and Thomsen-built boats, among them the 45-square-meter SKARVEN, which Erik Nielsen has owned since 1976. The deck details were different, but these hulls were hauntingly similar. Going aboard felt completely familiar. Were these PAX’s sisters? The answer seemed to be no; on my first trip, I found no records of PAX in Denmark.

JAN DAVIS

After a cold relaunching in February, the author slept aboard for two nights to keep watch over the bilge pumps, during which she had ample time for dreaming.

Over the next few years, I found out why. PAX was once named FIRECREST, which I hadn’t known before. That information, together with early photos of the boat and her distinctive tiller—carved in the form of a fish—finally proved that, sure enough, PAX was built in 1936 by Karl Thomsen to a 45-square-meter design by M.S.J. Hansen.

On two more trips to Denmark, I found pictures of Karl Thomsen’s boatshop in the city archives of Kalundborg. I stood on pavement near the railway station where the building once stood. I met Thomsen’s granddaughters, great-grandsons, and his last living apprentice, now retired. They told me that Thomsen always chose boatbuilding wood himself in the Jydderup forest. He often worked alone. No more than a few apprentices were ever allowed in his shop. So PAX was the product of his own hands. Articles from as early as the 1930s called him a perfectionist. Hansen, the designer, had the same reputation, and together they produced fewer than 20 spidsgatters in various classes. In 1931, Thomsen built AGNETE, the first 45-square-meter, followed by two more (CHARLOTTA and SKARVEN) in 1934 and 1935. In 1936, he built four spidsgatters—a 38-square-meter, two 26s, and a 45—and today all are still alive, including PAX.

While talking with the owners and sharing their stories with Thomsen’s family, one of his grand-daughters, now in her 50s, concluded, “In finding PAX’s story, you gave us ours.”

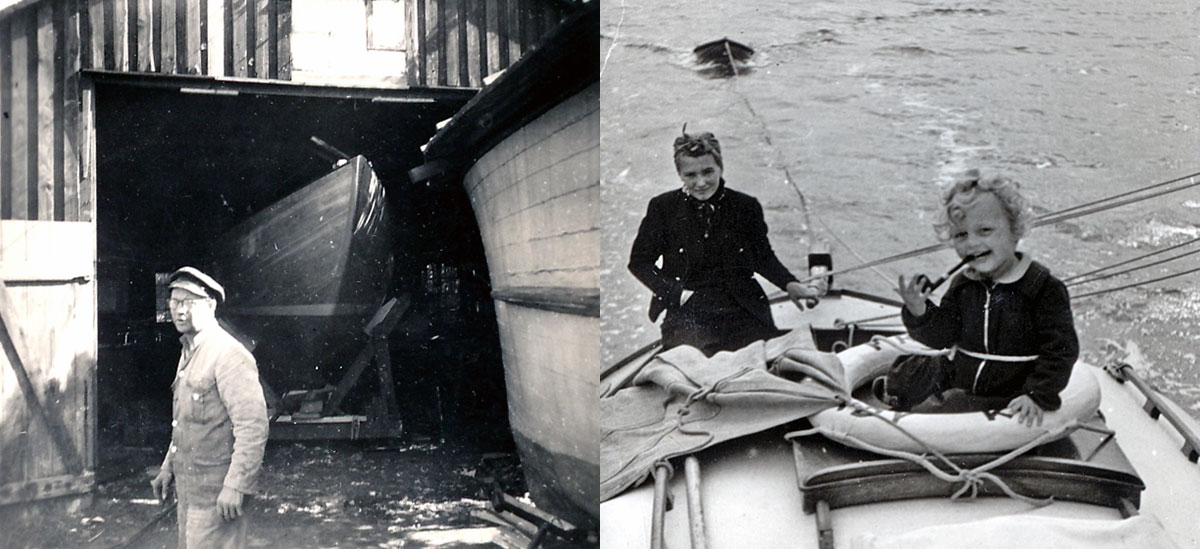

(Left) COURTESY OF JANET WYLIE, (RIGHT) COURTESY OF MERETE LEHMANN

(LEFT) PAX’s Danish builder, Karl Thomsen, completed his apprenticeship in 1915 and opened his own boatshop on the Kalundborg waterfront in 1932. He built at least 28 spidsgatters between 1932 and 1955; PAX was one of four he built in 1936. (RIGHT) PAX, then called FIRECREST, sailed every summer in Denmark during the Lehmann family’s ownership in the 1930s and ’40s, even through the Nazi occupation. This 1938 photo was taken by owner Aage Lehmann of his wife and young daughter, Merete, sailing north from Copenhagen toward their summer home in Roskilde Fjord.

Caretakers

Mine is only the latest of the lives that have been intertwined with PAX. As I learned more and more about her, I found that there was more to restoration than woodwork and more to value than a pedigree. I could feel and see the love of others. Her wood was a witness. Someone made that hatch. Someone knew why those frames were broken. I vowed to find who those people were.

My search for PAX’s history began where my personal history with her had started, on Vancouver Island. With some difficulty, I tracked down Janet Wylie, the only known previous owner, a mysterious and highly regarded woman shipwright who had owned PAX. There had been a serious fire on board in Sausalito, California, and she had rescued the derelict hull from the chainsaw. She trailered PAX to Bellingham, Washington, and spent five months installing a diesel engine, replacing keelbolts, reestablishing the sheerline, replacing the deck using plywood sheathed in ’glass cloth set in epoxy, building a new rudder, and installing new teak rubrails and toerails. She V-notched the plank seams, she told me, “to accentuate the beauty of the planking.”

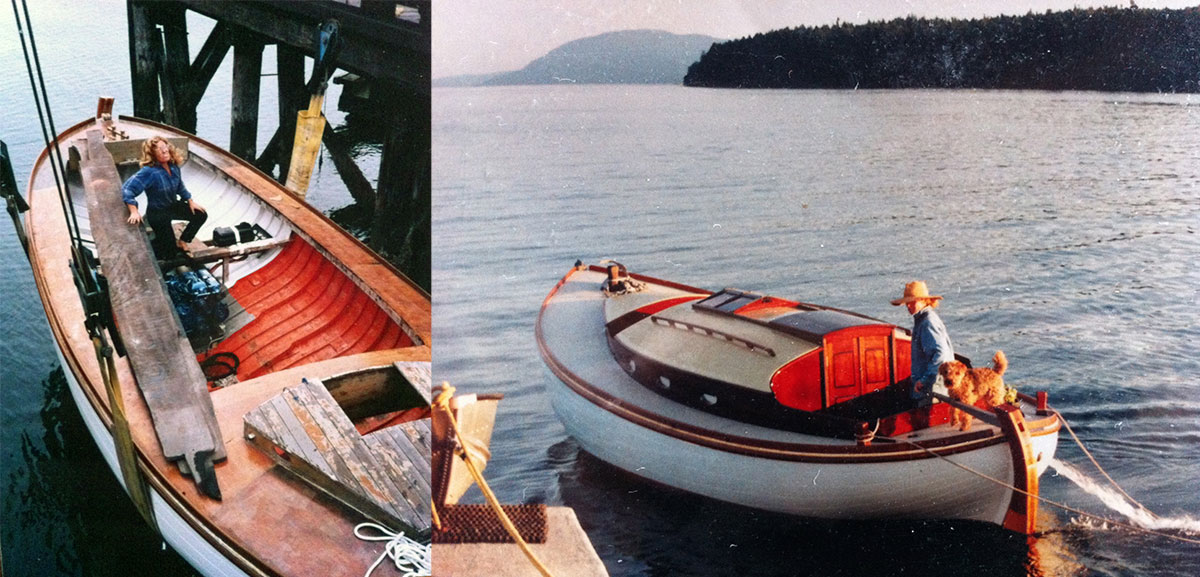

COURTESY OF JANET WYLIE (both)

After a fire in Sausalito, California, destroyed PAX’s original cabin and interior (LEFT), shipwright Janet Wylie saved the boat and transported her to Bellingham, Washington. She used the scant remains, old photos, and her design instinct to reconstruct the destroyed cabin and cockpit (RIGHT).

With her three young children and a dog, she then motored to Vancouver Island. For 14 years, she worked in a rustic boathouse, rebuilding the cabin, hatches, companionway, and cockpit coamings. No plans existed. She relied on her eye, badly overexposed black-and-white negatives of the burned-out interior, and the few remaining deckbeams to rebuild the cabin. She poured everything she had into the boat, then went cruising around the islands for years.

COURTESY OF ACE SPRAGG

PAX is one of several Danish spidsgatters often seen sailing along the historic seaport waterfront of Port Townsend. The sail number S45 denotes her original racing rating for the class carrying 45 square meters of sail.

Her leads took me to California: a shipwright in Sausalito; a musician in Dana Point; a couple in Laguna Beach. Over three years, I met former U.S. owners who had all loved PAX, and spoke of her elaborately carved tiller, of unforgettable sailing, and of her handsome curves. But bad things happened. Alcohol, cracked booms, damaged decks, fire, broken promises, and love transitions—the Sausalito shipwright lost his wife to cancer; the musician fell in love and moved to Italy; and the young couple sold the boat to buy their first house. None of the transactions between owners had gone smoothly. All were surprised and thrilled to know the boat was still sailing. The stories brought us all to tears. Apologies were made. Forgiveness tendered. The life-ring, bronze fittings, old files, and old pictures were dug out of closets and given to me, given back to the boat now known as PAX.

It was from the Laguna Beach owners that I learned about the former name FIRECREST. “The boat was his first love, so I had to be No. 2 from the moment we got married,” the woman said. “We both loved that boat. He found her in Wilmington, at Colonial Yacht Harbor, where boats go to die.” They had saved her, and their clue proved vital to solving the mystery of PAX’s origins.

Via email, Svend Erik Sokkelund of the Sundby Sail Club contacted 100 Danish wooden boat enthusiasts, this time asking about a spidsgatter named FIRECREST. One, a retired judge in his 70s, remembered FIRECREST and her carved tiller. He called his childhood sailing friend, Merete Lehmann, whose father, a dentist named Aage Lehmann, was the boat’s second owner. She emailed half a dozen photos of the boat taken from 1938 to 1946. One showed her as a toddler, sitting on the companionway hatch holding her father’s pipe while her mother was at the tiller. Every summer, the family sailed from Skovshoved, near Copenhagen, around the north end of Sjaelland and into Roskilde Fjord, but she knew nothing of subsequent owners. In September 2014, Merete flew to Port Townsend and sailed once more on PAX. “I hope he can see us,” she said of her father as we sailed. “It would make him so happy.”

Just as I couldn’t give up on the restoration, I couldn’t give up tracing PAX’s origins all the way back to the beginning. I knew that in 1936, cigar manufacturer Hans Christian Petry Bertelsen had curiously ordered two spidsgatters from Thomsen, the larger of which was a 45-square-meter named TONICA, that had only been listed for one year in the yacht registers before disappearing. Then, in 2013, during one last pass through the archives, Klaus Mathiassen found an error—a transposition of ownership—and by using engine specifications he was able to prove that FIRECREST and Bertelsen’s TONICA were one and the same boat. It was the last piece of the puzzle from Denmark. Klaus called Bertelsen’s grandson, and soon we had photos in hand. When I met the family in Copenhagen, three generations, by turns, read from the logbook of their ancestor’s voyage from Denmark to Belgium in 1937. That was the year he died, just one year after he had the boat built, explaining the brief entry in the registers.

KACI CRONKHITE

PAX has become a “regular” at the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival. The author was the festival’s director from 2002 through 2011 and the managing director of the Northwest Maritime Center (visible in the background) from 2005 through 2010.

The last owner in Denmark had the boat from 1946 to 1961. In 2014, I met Marlene Sandvad, who told me that her father and grandfather, Ole and Kjeld Sandvad, sailed all over Denmark and Sweden in those years. Then, the family sold the boat to an American, probably from Los Angeles, who so far remains an enigma.

In 2007, I had fallen in love with a beautiful boat. I gave her what she needed and sometimes all I had. In return, she taught me about boatbuilding, design, history, geography, and language and connected me with people in three countries who became friends and whose lives, like mine, were bent, steamed, and hammered into her hull. Together, we’ve been buoyed by her curves—the wood and craftsmanship touching our hearts across gender, language, class, and decade. Love, like a restoration, has no end on PAX.

Kaci Cronkhite is a traveler, writer, sailor, and passionate contributor to wooden boat endeavors worldwide. She is working on her first book, about PAX and her history. Connect via Facebook or her website, www.kacicronkhite.com.