Thinking About Interiors

The processes and details of construction

The processes and details of construction

CARIB II, a 52′ ketch built by A.C. Brown & Sons. Warm and inviting, CARIB II’s saloon offers welcome respite from a crisp fall day, when enjoying a cup of coffee freshly brewed in the adjacent galley is a pleasant alternative to sailing. This centerboarder, built in 1924 in Tottenville on Staten Island, New York, lives on today as one of Commodore R.M. Munroe’s best and final designs.

Boating in fresh air may be invigorating, but there’s nothing like settling into a cozy cabin at the end of the day. It soothes the spirit and is one of the great pleasures of being out on the water. There’s little so fine as having solid comfort in lovely surroundings with what you need close at hand.

With so many fine craft nearby for study and inspiration, we at WoodenBoat feel exceptionally lucky. We need only walk to one of the several boatyards in town or drive a short distance along the coast where myriad examples are being stored, repaired, or built new, to get our questions answered, our curiosity satisfied, or our energies renewed. This we sometimes take for granted and forget that few readers have such convenient access. The following photos are especially for you isolated readers, to help you learn the ways professional builders work with interior layout and joinery. (Perhaps builders of production and semi-custom yachts can pick up a few ideas as well.)

How things are built can be as engaging as the end product’s finished appearance, so you’ll see here many interiors in the process of being constructed. Aesthetically less lovely to look at than ones complete and appointed, they can be equally inspirational and even more instructive.

Before we begin examining interiors, let’s review some terms so my captions make more sense. We’re stuck with some strange words. We call the main cabin—the place where we sit to talk and eat—the saloon. This harks back to the spittoons and tufted leather of 19th century tycoon yacht owners, but despite that era’s demise, the term endures, occasionally being further corrupted into salon. Stateroom is another term that seems out of its time. I wonder why it simply isn’t called a sleeping cabin. A head can mean either the toilet or the enclosed room that contains it. This goes back a couple of centuries to when the allmale crew relieved themselves while sitting over the vessel’s bow squeezed between the headrails and side of the hull—or in some other place near the vessel’s head that afforded privacy and direct access to the universal dumping ground. Then there’s ceiling. In a house it’s the roof of a room. But in a boat, it’s the inner planking—likely a corruption of the word sealing since it seals off the hull’s frames from its interior. Cabins have soles, not floors as you’d expect. (Floors aboard a boat are the transverse frame members that cross the keel and help hold the two sides of the hull together.) The cabin can be inside or outside the hull. Inside it’s a living space; otherwise it’s a house-like structure built up from the deck. Low ones are known as trunk cabins, medium-height risings from the aft end of trunk cabins are called doghouses, and the really big ones that you walk directly into from the deck are (logically, at last) known as deckhouses. In review:

Saloon is a main cabin or living space

Cabin is a living space like a saloon, or an on-deck structure

Stateroom is a sleeping compartment

Head is either the compartment you’re in or the device you sit on when relieving yourself

Ceiling is sheathing inside the hull, not the overhead

Sole is a walking platform

Floor is a structural member for holding one side of the hull to the other

TRIVIA, a 46′ sloop built by Herreshoff Mfg. Co. Studying how especially admired boats were built has absorbed much of my life, and I highly recommend it for anyone interested in interiors. This is a museum-owned yacht whose original interior has remained miraculously intact, even to its distribution of paint vs. varnish. I love its ambiance, despite the wear. It’s patina, and it’s irreplaceable. You’ll find TRIVIA at the Herreshoff Marine Museum, Bristol, Rhode Island—back where she was built in 1902.

You can think of the interior of the hull as a container for whatever combination of bulkheads, partitions, flooring, and joinery you decide to fit in, yet one where nothing is level or square. But you need to sleep on a level surface, meals have to be made and eaten levelly so the dishes don’t slide off, and it’s hard to sit on a surface that’s cockeyed. Sinks and stoves and toilets come with the same need for levelness. And, generally, bulkheads and partitions that border and support these level surfaces feel better if vertical instead of slanted. So the trick is to have this interior boxiness (level and plumb surfaces) harmonize with the ever-curving shape of the hull. Achieving harmony between the hull’s many curves and the flat panels of the interior can be a challenge beyond pure function.

Basic functional objectives are to provide (a) a place to stand, (b) a place to sit, (c) a place to sleep, (d) a place for cooking, (e) a provision for human waste, and (f ) a place to eat, relax, and read. Standing headroom isn’t nearly as useful or necessary as are comfortable sitting and sleeping, and many a design has been wrecked in its pursuit. In a boat that’s small, you end up with unusually deep draft (to achieve a low cabin sole), or high topsides with much-too-high a trunk cabin. Good seating has its own height requirements, but by fiddling with seat height and slope (including the slope of the all-important backrest), comfort can usually be gained without compromising a boat’s outward appearance. For people of normal stature, 4′ vertical distance from cabin sole to the underside of deck or cabintop—or 3′ from the seat itself—is about the minimum; a bit more would be better. This calls for a sole that’s as low as practical, given the hull shape (lower means narrower, usually). Since most of the interior that follows will rest on the sole and you’ll need a place to stand while building it, it pays to establish the sole’s height and construct it early in the game.

Over many years, builders of coasting and fishing schooners and sloops worked things out to take advantage of the vessel’s deadrise by stepping progressively up and outboard as they built their settees and berths. You stand in the middle of the space under the trunk cabin near the stove and table, sit along the edge on settees, and for sleeping crawl way outboard under the deck. Cruising sailboats have evolved similarly to a logical and somewhat standard arrangement, but because there’s no cargo or fish hold, they generally have the saloon amidships where there’s the most width. With, say 11′ or more of beam, facing berths (port and starboard) are outboard high up and have settees along their fronts, with the table between, so there’s symmetry side-to-side. Narrower boats have to abandon this concept and adopt others, often employing ingenious berth-settee combinations. No matter what size boat, a pair of V-berths usually ends up way forward under the deck where headroom is unimportant and the hull shape fits the service. In a four-berth cruiser, call this the forward stateroom. With space enough between this stateroom and the saloon, there’s an enclosed head to port by the mast with lockers opposite and a passageway between. The galley, open to the saloon, goes aft near the companionway, and the engine hides under the self-bailing cockpit. An alternative is having the galley forward of the saloon so that quarter berths can be fitted under the deck on either side of the cockpit. This second option was more common back when a paid hand did the cooking and lived forward of the mast.

You’ll read about and no doubt see many other layouts—ones configured to the size of the boat and whether she’s sail or power. Most all function on some level, but some are more comfortable to be in and nicer to look at than others. As much as I’d like to set down guidelines to cover the ideal interior, its impossible to cookbook it because of all the options as to layout, construction, finish, and overall ambiance. It’s largely a matter of personal taste. Here are a few of my preferences:

Finishes—White paint, “let down” (by adding a touch of cream or light gray) is easier to live with than most of today’s out-of-the-can “refrigerator” whites. So is a satin finish, compared to gloss, in either paint or varnish.

Flats—Large, unadorned flats become more interesting if broken up by moldings or paneling. Edge trim that is shaped in cross-section is more interesting than rectangular. Raised panels and vertical staving are good alternatives to plywood expanses.

Metalwork—Brass or bronze fits shipboard use better than stainless steel or chrome. Stanchions made of the latter materials, unless tapered, have all the charm of an erector set.

Lighting—Opening skylights shed great over-the-table light. Well-placed deck prisms help eliminate darkness elsewhere.

Countertops—Plain wooden countertops of scrubbed ash or brushed metal ones are functional and pleasing to the eye.

Renderings and Mockups

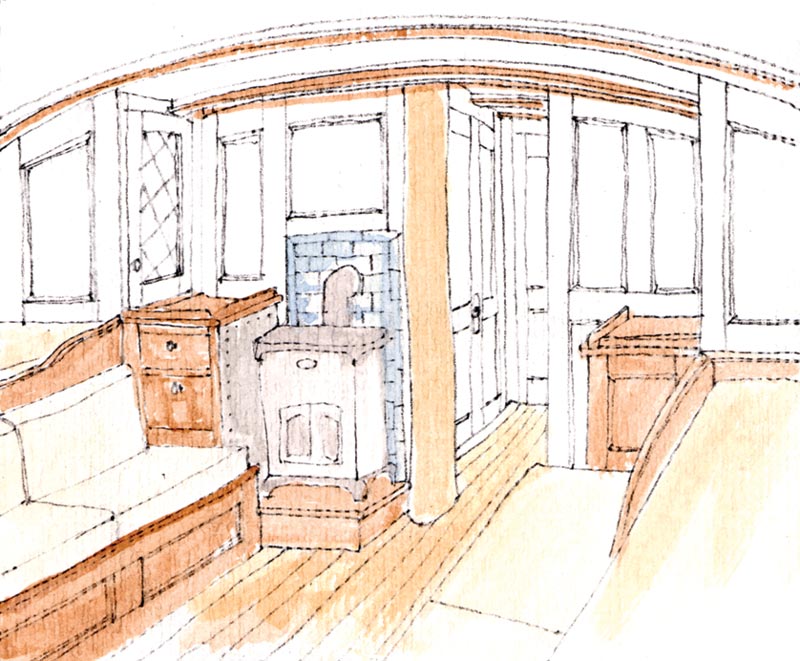

ANNA, a 56′ Sloop

Brooklin Boat Yard

While technical drawings (called a “plan” when viewed from above and an “elevation” when viewed in profile) give the details and dimensions of the various components, a perspective rendering brings the viewer aboard. This view of the saloon (by interior designer Martha Coolidge) of the recently launched Sparkman & Stephens sloop ANNA confirms that the wood heater, paneled bulkheads and settee fronts, and leaded-glass locker door work together to create a warm, inviting space.

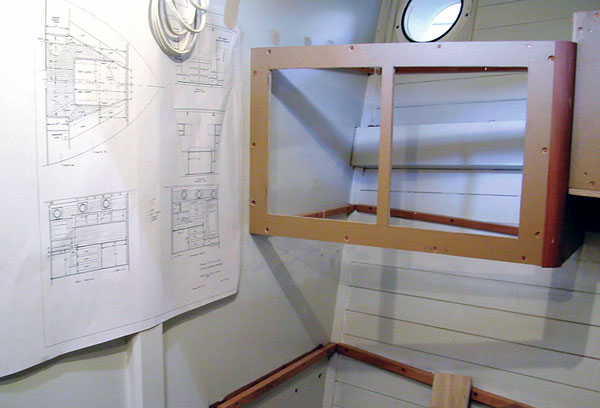

WINGS OF GRACE, a 50′ Ketch

French & Webb

A mockup, if carefully made can be disassembled and its pieces used as patterns for the real thing. Any notes, minor alterations (“make it like this, except…”), or appearance-related information simply can be marked directly on the pieces as has been done here.

SEMINOLE, a 46′ Yawl

Geo. F. Lawley & Son

Rebuilt by Brooklin Boat Yard

Full-sized mockups can be made of low-grade plywood or Masonite. You can get inside of these temporary accommodations and play house to confirm that what’s been drawn on paper will work. You can then make dimensional adjustments that in a confined space can make a huge difference. In this example, the empty hull, before restoration began, provided the mockup container and made everything more real. If you’re building new and don’t have an about-to-bejunked hull handy, you can still erect some kind of supporting structure to make the jump between viewing two-dimensional scale drawings and experiencing full size in three dimensions.

SEMINOLE

Having served its purpose, the old hull has been demolished, a new one built, and the proventhrough- mockup interior is on its way to being built and installed. Unlike the original, this one has plywood structural bulkheads attached directly to the laminated hull framing. (Planking is in two epoxy-glued layers.) For visual interest and a classic look, the bulkheads will be sheathed with faux rails, stiles, and panels.

The Hull as a Container

ALERA, a 43′6″ New York 30 Class Sloop

Herreshoff Mfg. Co.

Rebuilt by Boothbay Harbor Shipyard

Plywood structural bulkheads were in the future when this sloop was built in 1905. Back then, ceiling generally ran uninterrupted from bow to stern. The internal joinery that subsequently landed on it was lightly built (remember, this was before plywood was available), lightly attached, and contributed little if any to the hull’s strength. Ceiling covers the frames and eliminates having to notch berths, countertops, and other items around them. Laid in narrow strakes parallel to the sheer (which usually looks best) with the strakes sprung edgewise to fit against each other, ceiling gives you an attractive container for the joinery that follows. Narrow strakes can be milled on a tablesaw, while wider ones that resist edgesetting need to be tapered and fitted individually. In either case, the thickness need only be enough to be selfsupporting between frames, 1⁄2″, say, for 10″ frame spacing. The corners between adjoining strakes, if lightly chamfered (which looks better than a radius), will mask minor gaps or misalignments. Even though the strakes are pushed together wood-to-wood (which I think looks better than spacing them and leaving gaps), there’ll be plenty of frame-bay air circulation if you leave openings top and bottom. This particular boat’s ceiling will be capped, but the caps will be vented (as are TRIVIA’s, shown on the preceding page). This ceiling runs low enough for the platform (aka floorboards, or sole) to bear against it.

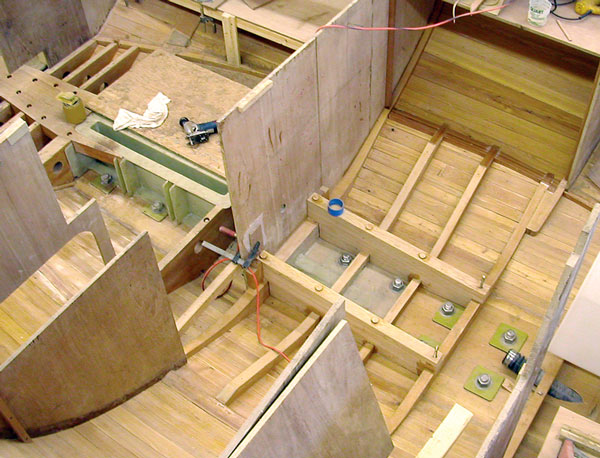

WIND ROSE, a 42′ Sloop

Brion Rieff, Boatbuilder

Tall rigs, synthetic sails, and highly tensioned shrouds and stays add dramatically to the loads any hull must bear. (I wish more sailors understood how quickly the seams of plank-on-frame wooden hulls can be forced open and made to leak simply by winding up too much on the turnbuckles or winching in too hard on the running backstays.) To resist contemporary rigging loads, modern hulls are made stronger. Skins are cold-molded and structural bulkheads, like those shown here, directly attach to the framing. Ceiling goes in later here and there, if at all. These boats are different critters altogether from pre-plywood, pre-epoxy hulls. But they can be made equally attractive belowdeck. This boat is a centerboarder whose trunk is housed below the cabin sole. Half floors (transverse structural timbers, not the platform you walk on) will soon brace the sides of the trunk, reinforcing it, as has already been done for the mast step that lies just forward. Ultimately, all will be hidden by the cabin sole, except for the engine itself. Cabin soles can either be level with a series of steps toward the hull’s rising ends or “sprung” to have a slight and continuous upward curve toward the bow and stern. The lower the sole is, the more headroom you’ll have—but, because of the hull’s sectional shape, the narrower it’s apt to be. In any event, getting the sole installed early, or at least installing its supporting beams so something can be laid over them to walk on, makes the work that follows easier to carry out. But despite the cold-molded hull’s shorter, bulkhead-to-bulkhead strakes of ceiling, they still should appear to harmonize with and echo the boat’s sheer.

LIGHT BREEZE, a 28′ Ketch

D.N. Hylan & Associates

Here’s a galley cabinet being built into a modified Rozinante whose hull has been ceiled back only as far as the cockpit. The bulkhead is plywood for strength but has been sheathed on both sides with thin teak planks about 3' wide, run vertically. Light wooden cleats serve to attach cabinetry to the hull. Cleats of medium-density wood like mahogany or Douglas-fir hold fastenings well, yet can be planed and chiseled without too much effort. These cabinets are being built in place, but depending on their size, shape, and location, others can be constructed as subassemblies and installed after completion.

Leaving the Top Off

HOI AN, a 50′ Sloop

Brooklin Boat Yard

Working on an interior becomes much more efficient without the cabin in place. This built-off-site trunk cabin goes on only after most interior work has been finished and painted. Here, the push-button-controlled electric hoist makes the fitting an easy matter.

APHRODITE, a 74′ Commuter

Purdy Boat Co.

Rebuilt by Brooklin Boat Yard

Some cabins are too long or otherwise don’t lend themselves to being built as subassemblies, so are built in place. Here, the sides were needed to receive the bulkheads, but the top came later. APHRODITE’s speed came from being kept light as well as having plenty of horsepower. Her bulkheads and partitions, for example, are of vertical tongue-and-groove softwood in a single thickness and, as you can see, their tops have been left long and are held in line by temporary cleats until there’s a cabintop structure to attach to. Because the hull itself has been leveled and plumbed, spirit levels can be used in setting up the joinery.

MARJORIE, a 59′ Ketch

Brooklin Boat Yard

Most new cold-molded yachts have had their bulkheads placed for double duty: to divide the hull into various compartments and to strengthen it. A third purpose is to help provide the shape over which to lay up the planking—usually a combination of glued-together fore-and-aft strips and diagonal veneers. More bulkheads may be added after the hull is turned upright. Here you can see the early stages of such an interior. In the foreground, patterns are being made for the cockpit, which will be built as a subassembly. Similar patterns of hotglued, thin plywood will be made for various components of the living spaces so that these pieces can be made in the shop, with the confidence that they’ll fit the boat when it’s time to install them.

Joiner Bulkheads

ORIOLE, a 43′6″ New York 30 Class Sloop

Herreshoff Mfg. Co.

Rebuilt by Cannell Boatbuilding

For beauty, it’s hard to beat rails, stiles, and raised panels. I guess that’s why so many articles and books contain instructions on building them, although they’re mostly for houses. You always build on the bench as flat panels, then do the installation and attaching afterwards. I can’t recall whether this bulkhead was built to an exact template or made with extra wood for fitting. Either way, it will screw to a quarter-round softwood cleat that’s been fastened to the ceiling—a scheme that’s sufficiently secure for joinery, but not for added hull strength. Hulls like this flex and change their shape a little over time, so these kinds of bulkheads “float” as conditions change.

YOUNG MISS, a 46′ Buzzards Bay

30 Class Sloop

French & Webb

With small pieces of thin plywood scribed in place one at a time and connected with hot glue, you can make an exact bulkhead template. Other builders prefer using the joggle-stick approach.

YOUNG MISS

With the bulkhead laid out full-size on an assembly table, the size and shape of each piece can be easily and accurately determined. Then, after roughing out, each piece is clamped to a plywood base and run past a shaper to fashion its edges and ends. Floating tenons, glued in place, reinforce the rail-to-stile joints, and the panels themselves are captured by grooves where they’re free to shrink and swell with changes in humidity. Less-well-equipped shops can turn out equally handsome paneled bulkheads using routers, tablesaws, and hand tools—and, generally, more labor.

ENTICER, an 85′ Motoryacht

John Trumpy & Sons

Rebuilt by Brooklin Boat Yard

Flat-panel bulkheads and partitions can be enhanced by gluing on rails and stiles to simulate a genuine, oldtime fabricated panel. Once the basic MDO panel is in place and guidelines are marked on it, faux rails and stiles can be glued as shown using sheetrock screws and buttons to apply clamping pressure. (MDO, or Medium Density Overlay, is a waterproof, paper-faced plywood; it accepts paint without the raised-grain issues of plain plywood.)

Cabinetry

APHRODITE

A wooden cleat screwed directly to the hull framing, since there’s no ceiling here, will support the outboard edge of this berth. Saving weight was key, so the ceiling will exist only above the berth top, where it’ll show. The fore-and-aft berth front was built in the shop to the drawings, then fastened into place so the remaining cleats and joinery could use it as a reference or a point of attachment. If you keep up with the painting as you go, as has been done here with the hull and bulkhead, you’ll get more thorough coverage.

ENTICER

Based on the galley/dinette arrangement drawing, the hull ceiling has been taped to indicate where each item of joinery attaches. Panels are of MDO, which, in combination with natural wood that can be varnished, has proven to make an attractive and durable interior

ENTICER

Joinerwork aboard ENTICER is now pretty much complete, and the painting and varnishing are well along. A lathe-turned post supports the inboard end of this cabinet assembly, and the unit itself is all ready for its hinged doors. The temporary countertop, shown in the previous photo, has been set aside so the maple butcher-block one can be installed.

ENTICER

Cabinets like this, where the back and one side are formed by the boat’s structure, are best built right in place. Size and location were depicted on an arrangement drawing, here taped up for reference, but the cabinet construction was left to the builder.

Details

ALERA

Raised panels and hanging knees make good companions even though they are not directly connected. The knee and the sheer clamp behind it are basic hull structure, while the bulkhead is pure joinery, having only to be strong enough to support itself.

ENTICER

Sheathing over unsightly structure, in this case a steel support beam under the deck, is sometimes desirable. Here, the box-like sheathing has been enhanced by an overlapping bottom, nosed off, and a molding that makes a visual transition into the deck beams above. For emphasis, the beams have been given varnished mahogany face trim that matches the cornerposts and the trim around the door openings. While hull framing gets hidden, deckbeams are what you stare up at from your bunk and should be finished more carefully. You’ll also like the decking itself better if, instead of painted plywood, you can look up and see seams and strakes. It’s all about making an otherwise plain surface more interesting.

ALBACORE, a 40′ Ketch

Geo. F. Lawley & Son

Rebuilt by Benjamin River Marine

Many structural elements, such as hanging knees, deck beams, sheer clamps, and shelf supports, if well proportioned and finished, are really nice to look at so there’s no need to cover or otherwise hide them. Even the bolt ends and nuts that stand proud along the edge of this knee, because they’re evenly spaced and carefully cut off, look well and demonstrate a superior level of workmanship.

ALBACORE

Raised panels, whether afloat or ashore, are revered for their charm and because they break up an otherwise plain area into a gathering of rectangles that can be made to taper and curve so as to complement the hull’s internal shape. Curved instead of sharp corners, as in this settee, not only look well, but are less likely to wound if one is thrown against them. This cabin sole is of wide teak boards, left bare, and is one of the most practical. Teak neither rots nor cups, and it retains its lovely natural color without paint, oil, or varnish.

VELA and ANNA—Different boats, different interiors

Here we have two boats of similar overall length but of vastly differing styles. The first, VELA, is a 50′ gaff sloop designed and built (with Twig Bower) by Haddie Hawkins for use as a charter vessel in Maine and Massachusetts. The other, ANNA, is a newly launched 56′ Sparkman & Stephens-designed sloop built by Brooklin Boat Yard and modeled on a legendary S&S predecessor, STORMY WEATHER. The following photographs illustrate some of the details that make these boats’ interiors so suited to their individual purposes.

VELA

“Adjustable” is what builderowner Hawkins calls this interior, which he rearranges every so often to meet the changing needs of his family and charter business. Although this means gutting and beginning again, the carpentry is so basic that the task becomes an adventure instead of a dreaded chore. Vela’s sole is unfinished ash, notched around her exposed sawn frames—to which most of the joinery is fastened. Systems are simple and exposed for access. Wood is mostly native. Berths are sized to fit standard mattresses and bedding.

ANNA

On the elegant end, the joinery here abounds with raised panels and varnished wood. As mentioned on page 66, a full-scale mockup and colored renderings allowed the owner to confirm and tweak the design, and thus avoid expensive alterations and disappointments later on. Detailing is superb—a delight to the eye—and there’s a wonderful distribution of light and dark tones, generally with the brightwork below the beltline and paint above. And, with a skylight and deck prisms, there’s plenty of natural light.

Maynard Bray is technical editor for WoodenBoat.