Perfect Adaptation

Back in 1995, to research an article on the magnificent reconstruction of the 68' LOD Fife cutter BLOODHOUND (see WB No. 128), I visited Marina del Rey in Los Angeles County, California. BLOODHOUND was then berthed in a slip there (she now hails from Massachusetts; see WB No. 287). Based on a British racing design from 1874, she was a stately anachronism in a veritable city of mostly modern yachts. Indeed, Marina del Rey is the largest human-made yacht harbor in the United States, and home to some 5,000 boats. Experiencing the waterway is downright Venetian—in the right boat.

Bob Gilbert, who had built BLOODHOUND with a crew of experts and owned her for more than 20 years, was an aficionado of classic watercraft. He had just the right boat in which to explore the slips and canals of Marina del Rey: a Pulsifer Hampton, an open, inboard-diesel-powered, center-console boat. One evening, after sailing and interviews, Bob handed me the keys to his Pulsifer Hampton and I set off alone, in a misty half-light, to have a look around. I explored for about an hour. It was a peak experience, well remembered nearly

30 years later.

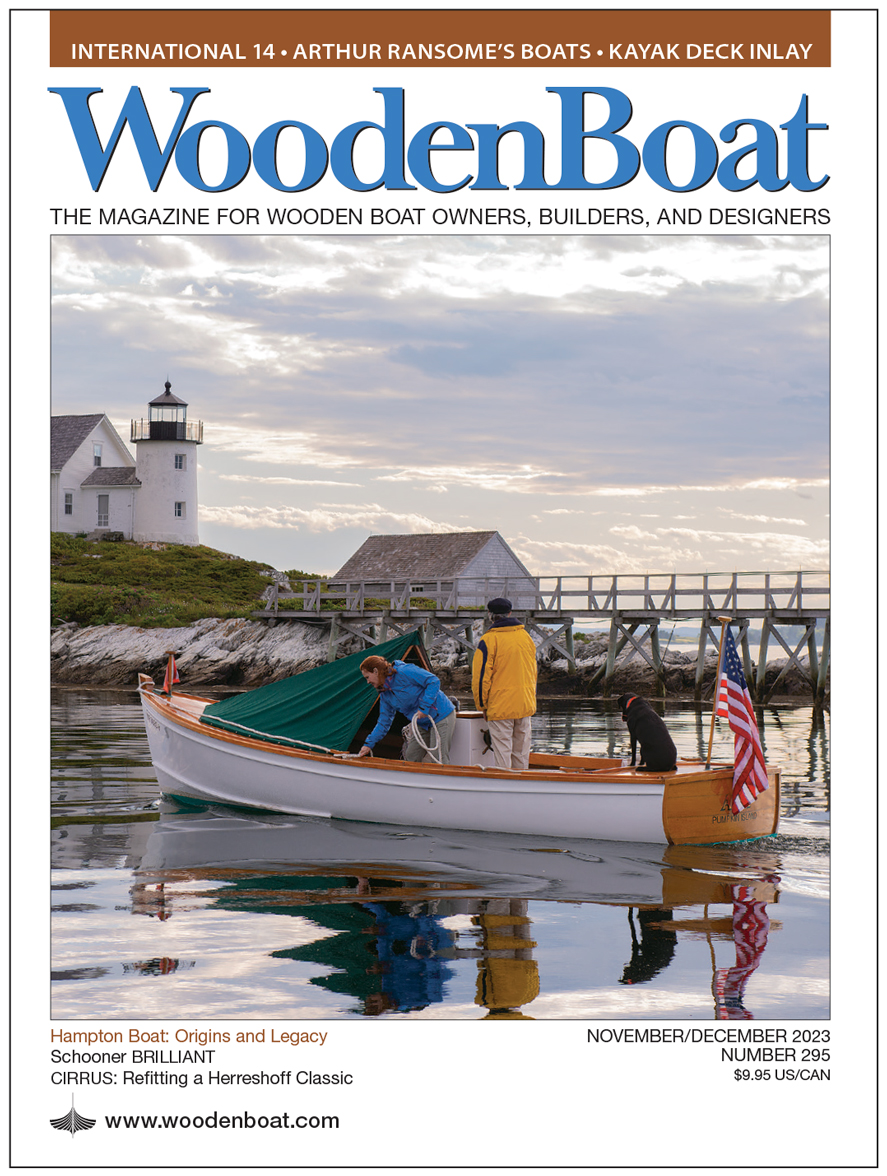

The Pulsifer Hampton, named for its builder, Dick Pulsifer, is the motorized evolution of a sailing workboat that originated in and around Hampton, New Hampshire, in the early- to mid-1800s. A pristine example is seen nosing into its berth at Little Deer Isle, Maine, on the cover of this issue. In his article about the origins, evolution, and legacy of Hampton boats (page 64), Stan Grayson writes that the earliest known recorded reference to the type was published in 1835 by the American naturalist James Audubon. However, he further states that, “[i]n the general absence of written records, the origins of the Hampton boat are shrouded in the same mystery one encounters when researching almost any 19th-century working craft. Instead of archival material, oral tradition—basically folklore with all its shortcomings—is what there is to go on.”

As you’ll see, Stan does a remarkable job of weaving together the spoken threads of the Hampton boat’s history, its evolution as a sailing craft, the spinning-off of a square-sterned version from the early double-enders, and its adaptation to internal combustion engines at the turn of last century. “The square-sterned Hampton,” he writes, “with its relatively high bow, good freeboard, and greatest beam starting aft of amidships was well-adapted, almost tailor-made, to accept an engine.” That brought to my mind a conversation I had with Dick Pulsifer around the time he launched hull No. 100 of his line of Hampton boats. He made some tweaks to the design around that time—increasing the stern’s width by just an inch or two. In an age when annual tweaks to cars, production boats, appliances, computers, and nearly all manufactured products are expected for the product to remain relevant, the motorized Hampton boat has not changed. It has not needed to.

Indeed, the humble Hampton boat remains as perfectly adapted to a variety of places, from its original inshore waters of New England to the labyrinthine maze of southern California’s Marina del Rey.

Editor of WoodenBoat Magazine