September / October 2019

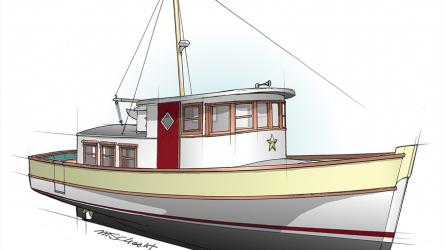

From One Classic to the Next

The author and his wife, Christina, sold their classic fiberglass-hulled Swan 38, PIRATE, in 2010, after years of voyaging. They then embarked upon a search for “a boat beautiful and old-fashioned, a boat in which we could have peace and freedom away from gadgets and easy comforts, relying mostly on the old arts of seamanship.” The Concordia yawl WESTRAY answered that wish.

When we left PIRATE, the Sparkman & Stephens–designed Swan 38 we had owned for 22 years, in Finland in 2010, I asked myself “why?” My wife, Christina, asked the same question. We had a boat made for a lifetime. How can you be both determined and puzzled at the same time? I knew it was the right thing to do, but had not managed to articulate the reasons. When people questioned me, my only answer was a shrug. Now I think I can provide something resembling a rationale.

I had the feeling that our years on the boat, given the many miles we had sailed and the oceans we had crossed, had arrived at a point of completion. The Swan had given us all we wished from her, and then some more. Completion in this sense meant accomplishment, reaching a sort of existential destination—in short, a fulfillment. The time had come to let her go, but not in just any way, to anyone, in any place.

Completion, or closure, meant also homecoming for the boat herself. We had her restored in Finland, where she was born, in a place where classic Swans were produced, and surrounded by people who had shaped her hull and built her spars in 1974.

And so it happened. After a small interlude in the Mediterranean under her new owner, PIRATE returned to Finland, where she was destined to stay. She changed hands once more, to another Finnish sailor, as if looking for a more perfect master, which she found.

To read the rest of this article:

Click the button below to log into your Digital Issue Access account.

No digital access? Subscribe or upgrade to a WoodenBoat Digital Subscription and finish reading this article as well as every article we have published for the past 50+ years.

ACCESS TO EXPERIENCE

Subscribe Today

1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION (6 ISSUES)

PLUS ACCESS TO MORE THAN 300 DIGITAL BACK ISSUES

DIGITAL $29.00

PRINT+DIGITAL $42.95

Subscribe

To read articles from previous issues, you can purchase the issue at The WoodenBoat Store link below.

Purchase this issue from

Purchase this issue from