The Bights of Andros — Part Two: North & Middle Bights

I sold my pilot schooner LEOPARD in late 1998, during my fight with cancer, and several years went by before I built my next cruising sailboat, T’IEN HOU. I launched her in early 2002, and in ‘03, ‘04 and ‘05, ran through the Bights of Andros with her.

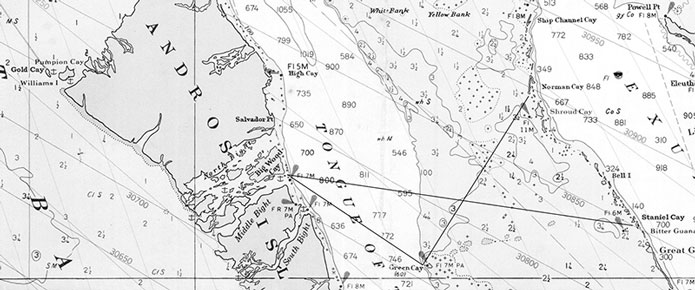

In early 2003 we sailed T’IEN HOU to Bimini to enter the Bahamas (as I usually do), continuing to Gold Cay off Andros. In my previous Blog you can see my penciled-in course line on the chart for the long day-passage between Bimini and Gold Cay. Because T’IEN HOU has even less draft than LEOPARD (three feet), we circled the island looking for a more protected anchorage, and found a good spot in a shallow cove due east of the cay.

On these voyages I decided to try my luck with North and Middle Bights, even shallower than South Bight. Harry Kline’s instructions (in Yachtsman’s Guide to the Bahamas) describe switching from North Bight to Middle Bight about halfway across Andros, and that is what we did, although it was unclear exactly how. Once again it was difficult to find the west entrance, but a shallow turquoise channel into a small bay lead us to numerous possible leads, and by trial and error we found our way into a narrow opening, which I named the “keyhole.”

The North and Middle Bights of Andros, courtesy of Google Earth, showing my waypoints.

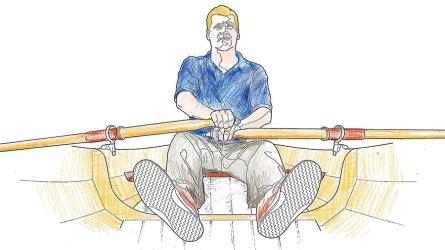

After the keyhole, things became more complicated and confusing, as we could see several possible channels, some of which vanished in shoals only inches deep. We proceeded by trial and error, with bow lookouts.

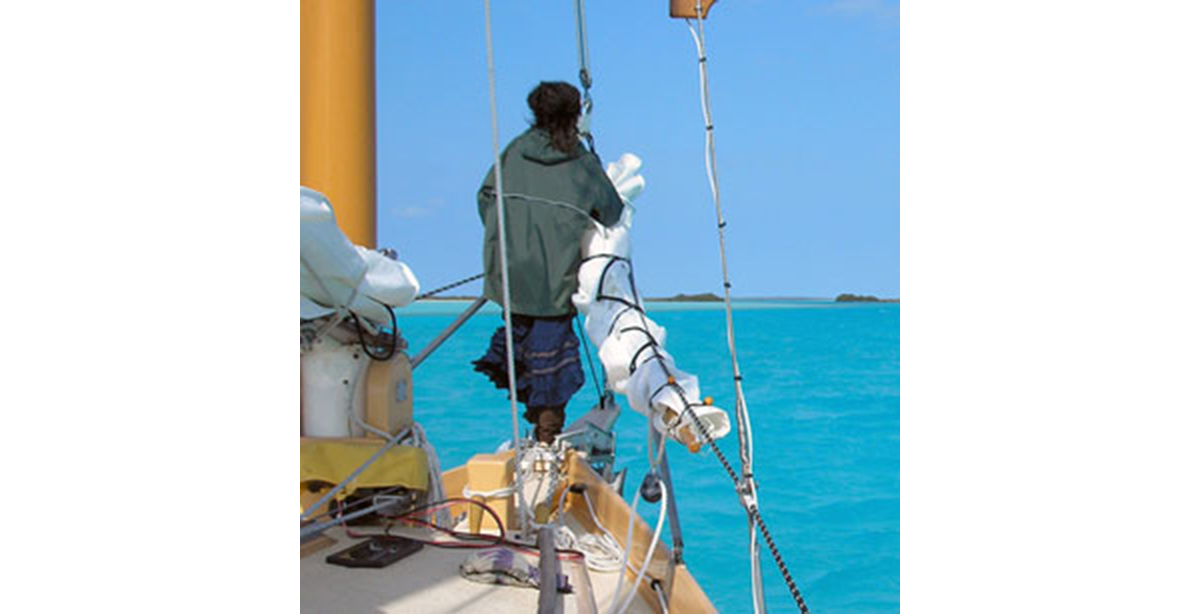

Seeking channels inside the west entrance to North bight (T’IEN HOU, 2005.

Well inside the Bight, the shorelines on all sides retreated, leaving us once again in a huge white lake (as in South Bight), with indistinct, distant land features. We proceeded in an easterly direction, looking for something—anything—that would tell us where to go. Finally, on a descending tide, we anchored for the night. I took a GPS reading for our anchorage, and it has been useful to me ever since. I called this “White Bay Anchorage” and included it in my waypoint list.

Weighing anchor in “White Bay” (T’IEN HOU, 2005).

The water depth in North Bight was frequently less than three feet (our draft), and we simply plowed through it, leaving a long white cloudy wake behind us as we snaked around looking for deeper water. The depth sounder was completely useless. This takes a certain amount of nerve, and is probably not for the weak-hearted. Eventually I was able to identify Cedar Island, more by guess and by golly than anything else. Essentially I assumed what I saw to be Cedar Island, and we proceeded from there as if it were. It worked: We were able to further (tentatively) identify shoals, rocks, and islands, as we meandered around looking for likely passages.

The maze of estuaries, islands, channels, rocks and distant shorelines was really confusing, and from deck level everything on the horizon blended together. All we knew was that we were in the middle of a big, strange, beautiful place, with absolutely nothing to tell us where we were or where we were going, so we just kept working our way eastward. I often stood on T’IEN HOU’s pilothouse hardtop to gain the perspective granted by elevation. I also had a lookout on the bowsprit, and a helmswoman below me following our confused instructions… it was wonderful!

Bow lookouts searching for the true channel approaching Middle Bight.

When we were almost through to the east side, we passed what might be construed as the only aid to navigation anywhere in the Bights—a rusted out hulk that might have been a steam boiler. Many years ago Andros was logged for its extensive stands of Cedar—perhaps this was part of a 19th century steam tug?

After the boiler we eventually emerged into a long shallow bay (below Big Wood Cay), which opens onto the Tongue of the Ocean. We were losing our light, and finally anchored for the night in heavy rain showers (anchorage 02 in my waypoint list). The next morning, on the flood tide, we ran aground several times trying to find a way out. I eventually learned to stay to the middle of the bay, but years later still ran IBIS hard aground trying to get out. In the mouth of the bay is Gibson Cay, and just to the north of it is one of the old Autec Stations, from which torpedoes used to be tested in the Tongue of the Ocean. I made the mistake of trying to enter the old marked Autec channel, and ran hard aground on a very nasty shoal that divides the Autec channel from the natural channel, which lies just north of Gibson Cay. The tide floated us off. Entering and leaving the east entrance to Middle Bight, you must stay in the natural channel south of the Autec markers and hug Gibson Cay.

A few miles further south is the friendly settlement of Moxie Town. Returning single-handed from the Exumas in T’IEN HOU one year, I was very nearly out of fuel and cash, and I dinghied over to the fuel dock in Moxie Town with my 5-gallon diesel jugs. It turned out that the dock couldn’t process credit cards, and the nearest ATM machine was on a different planet. So the fuel attendant GAVE me fifteen gallons of fuel. Can you imagine that happening anyplace you have ever been? I love Andros!

Andros and the Bights, showing two course options to the Exuma Cays (soundings in fathoms).

From Middle Bight it is a straight ESE run across the Tongue of the Ocean and the Exuma Banks to Staniel Cay in the Exuma chain. Once on the Banks, you will pass the two old Decca towers (excellent landmarks) just north of your route. It’s a long haul—80 miles—and I usually motorsail at no less than 7 knots to make it to the Happy People Marina in time for Happy Hour. Alas, this is no longer an option, as Ken Rolle & his wife have passed away—but the excellent Staniel Cay Yacht Club is alive and well. From Staniel Cay you have the whole outer Bahamas and points east right at your fingertips. George Town, Great Exuma (at the bottom of the chain) is two day-sails away.

In 2010, first mate Delfine and I sailed my new sharpie schooner IBIS on this route, from Key Biscayne, Florida, to George Town, Great Exuma, proving that a flat-bottomed sharpie was capable of motorsailing into strong trade winds and ocean seas.

IBIS’s first mate Delfine in 2010 (Reuel’s Angel #1).

In 2012 I sailed IBIS in even stronger easterly trade winds, with first mate Joee Sym. We departed Middle Bight in 25- to 30-knot winds and 6- to 8-foot seas right on the nose, and finally stayed on the port tack to fetch Green Cay, which I had wanted to visit for many years. This small uninhabited cay had no protected anchorage, so we anchored in the lee as best as possible, and spent an uncomfortable night rolling. Nest morning, we took the starboard tack up to Norman Cay, the closest we could point, and thus entered the Exuma Chain.

* * *

Getting from South Florida to the popular cruising destination of George Town is therefore efficiently accomplished by sailing from Biscayne Bay or the Florida Keys to Bimini (or points south), to Gold Cay (or Williams Island), through the Bights of Andros, to Staniel Cay, to Little Darby Island (or Lee Stocking Island), and finally to George Town, Great Exuma. In LEOPARD, T’IEN HOU, and IBIS (weather permitting), we typically took seven or eight days, stopping to anchor every night, to make this trip. The reverse trip can be made even more easily with the trade winds behind you (I once did it in six days). One of the many advantages to this route is sailing southeast (on one long tack) from Bimini in the lee of Andros.

In fifteen years of exploring Andros’ west coast and three Bights, I have never seen another yacht anywhere except just inside the eastern entrances of South Bight and Middle Bight. One time we saw a local Bahamian guide-boat taking fishermen-tourists to a bone-fishing flat, and twice we have seen small local boats near an island not far from that rusty old boiler mentioned earlier. I have never seen a plastic jug or a beer can in the Bights (may it, please, stay that way).

North Bight (T’IEN HOU, 2005).

The attractions of the Bights include excellent bone fishing, bottom fishing, collecting conch and spiny crayfish (Bahamian lobster), sponging, exploring untouched islands, bays, “lakes” and estuaries, diving in the deep “blue holes,” and just enjoying the solitude of being in a wilderness. When you tire of this, there are the tiny and charming settlements and hotels to visit ashore on the east coast of Andros.

In Navigating the Bights, keep in mind that it is essential to play the tides. Because of the difference in times, it is possible to “flow through” with the high tide from east to west, and work against the high tide from west to east. Timing is everything. Often it is necessary to anchor in the middle of a Bight and wait for the next high tide. Fortunately there are anchorages at both ends of all the Bights suitable for arrivals and departures. After 15 years I still get confused in the Bights, even with my charted GPS waypoints. I also still run aground. The mysteries are still real. I admit that these things appeal to my love of gunkholing—I live for the challenges.

The Bights are beautiful, mysterious, intricate, and rewarding to navigate. While it is sadly true that very few monohull sailboats can even consider these passages, a majority of the ever-growing contingent of cruising catamarans (and trimarans) can certainly navigate the Bights, as can many small cruising powerboats. The extreme upper limit of draft is four feet, but three feet can be carried through without plowing up too much “mayonnaise.” Two feet can nearly go anywhere, anytime.

8/18/2015, Appleton, Maine