The Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter

Where skill is the object

Where skill is the object

Nils Kjetil Torvik

The Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter—Ships Preservation Center—is located on Norway’s Hardangerfjord in the town of Norheimsund. It began as an effort to restore one vessel, MATHILDE, and has grown to become one of Europe’s principal vessel restoration establishments.

Olav Bjoerkum

The center still owns MATHILDE, using her for summer camp excursions and for charter.

A visitor to the Norwegian town of Norheimsund searching for the Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter need only follow his nose: the smell of Stockholm tar will lead to the place. The Fartøyvernsenter, or Ships Preservation Center, is a cluster of immaculately painted raw-umber and yellow-ochre shop buildings sitting on spotless waterfront grounds set against the glacier-topped mountains and rolling green hills of Norway’s Hardangerfjord. Its façade has the air of postcard-perfect microcosm of traditional Norwegian maritime industry. Inside the shops, where handmade rope spins from a quarter-sized loft, and site-forged iron rivets and roves fasten the planks of faerings—the staple small boats of the region—it looks and sounds no less so. A steady succession of large wooden (and a few steel) vessels have found new lives here over the past 20 years—heroic reconstructions by career-minded apprentice shipwrights.

There are boats on exhibit, but they are not what this place is intent on preserving. The Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter, you see, is not a museum in the usual sense—not a distillation of static objects arranged to tell a story. Nor is it a profit-minded, time-, motion-, and material-obsessed ship-repair and boatbuilding business. Efficiency is important, for sure, but not simply for the bottom line; good work performed in a timely manner is a function of ability, and that, ultimately, is what this place is all about. At the Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter, traditional maritime skill itself is the product.

“No one can understand us. We don’t fit in the museum world,” said Geir Madsen, acting director of the Fartøyvernsenter. “It was hard in the beginning,” he continued as we sat outside the visitors’ café one day last June, discussing the place’s evolution from a single ship reconstruction project to a multipurpose educational institution. I had met him once before, 10 years earlier, at this very place, when the center was struggling to fulfill a then-changing vision. “The local people were against it, and I can understand that. All of us were looking like hippies,” said Geir, who, with close-cropped blond hair and angular jaw, now looks like the musician Sting. “We were bringing in rotting boats. You can imagine what it looked like. No one could have imagined it could look like this.”

Courtesy Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter

Peter Helland-Hansen (left) and Haavard Gjerde display the Fartøyvernsenter’s small-boat production at midwinter. Helland-Hansen runs the small-boat shop, which mostly builds faerings, or four-oared boats, to a local design.

The Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter (HFS) began in 1984 with this simple intent: rebuild a traditional Norwegian vessel and, in the process, light a fire in the hearts of some wayward kids. The vessel was MATHILDE, a freighter built in Hardanger and originally rigged as a sloop. Launched in 1884, she’d spent a long dotage hauling freight along the Norwegian west coast under power alone, her spars cut away in the 1930s.

One hundred years after her launching, her tired hulk came into the hands of a group of idealistic visionaries led by a man named Torbjörn Kaarbö. Calling themselves Stiftinga Hardangerjakt (The Hardanger Sloop Foundation), they purchased her with an eye toward restoration to original configuration. The work, they supposed, would take two years, and would be accomplished by a handful of direction-hungry adolescents—a job-training mission under the supervision of able shipwrights. “At that time,” Geir Madsen recalled, “there were lots of unemployed youth [in Norway]. “That fit very well into the MATHILDE project.”

The job would take place at a defunct furniture factory on the Norheimsund waterfront—a place that was to have been torn down, the land given over to industrial use. The local government owned the property and, despite the protests of some residents, agreed to lease it for the restoration of MATHILDE. The 72′, 71-ton vessel was hauled on a newly built slipway, and the ugly job of ripping out began. Geir Madsen arrived that year, a fresh-faced apprentice just out of university and planning to stay only a short time.

The projected two-year schedule was a pipe dream. The restoration took five years of hard, heavy work, requiring replacement of over 80% of the vessel’s timber. And the training effort, although successful for this particular job, did not survive as a business model. The demands of high-quality big-vessel work conflicted with those of youth training. In youth training, the emphasis is on building a person—and not necessarily a technically skilled one. “Sometimes we had to cut away what had been done,” recalled Geir Madsen of those early efforts to hold work to an acceptable standard. Career-minded apprentices, rather than at-risk youth, were increasingly plugged into the vessel restorations, while accumulating tools and skills in Norheimsund attracted more projects similar to the MATHILDE rebuilding. The single-ship effort morphed into a center for such restorations, and a name change ensued to reflect that mission.

Courtesy Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter

The Fartøyvernsenter’s big-vessel restorations are typically multi-year projects. Above left—Kasper Krogh Hansen fastens planks for the deck of the cutter IDSAL, restored at the center from 1999 to 2002. The vessel was built at Great Yarmouth in 1974. Above middle—The ketch SVANHILD of 1889 during restoration, about ten years ago. She is currently being fitted out in the town of Florø, on Norway’s west coast. Above right—The double-ended fishing boat SOLSTRAND, restored at the Fartøyvernsenter between 2001 and 2003, was built in 1936. She now hails from the Flekkfjord Museum.

The youth training component, however, did not fade. Rather, the Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter diversified into a multifaceted program populated by full-time apprentices, as well as adolescents who live with local families. Forty-five boatbuilders have been certified through the HFS’s apprentice program to date, and many wayward youth have passed through its doors. How many? “Several hundred,” said Geir, furrowing his brow for a number. And then “I don’t know exactly…we need quite a lot of time to change their situation.” How do they arrive here? “They are both directed to come here, and they choose to—for one to three years. Here they realize they are part of a working place. They have a salary.”

Courtesy Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter

BROEDRENE AF SAND departs Norheimsund in 1999 after a full, multi-year restoration. The 50′2″ sloop was built in 1840.

Over a decade, the place expanded physically, too. The original core of land is still leased from the local government, but the HFS purchased adjacent land in the late 1980s, bringing the total area to about two acres. Several large vessels adorn the waterfront, a shed, and a slipway—all restoration works in progress, all open for public viewing. The Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter’s name promises a big-boat mission, and it delivers one. But there is a successful small-boat program here, too.

Consider the faering. The word means, simply, “four-oared,” and the boats themselves have a proportionately simple appearance. Shaping them is left to the builder during construction; it is traditionally accomplished by eye in a process that, like dancing the tango or flying aircraft, must be made intuitive by repetition. Peter Helland-Hansen runs the Fartøyvernsenter’s small-boat shop, and in that capacity he has built 60 faerings.

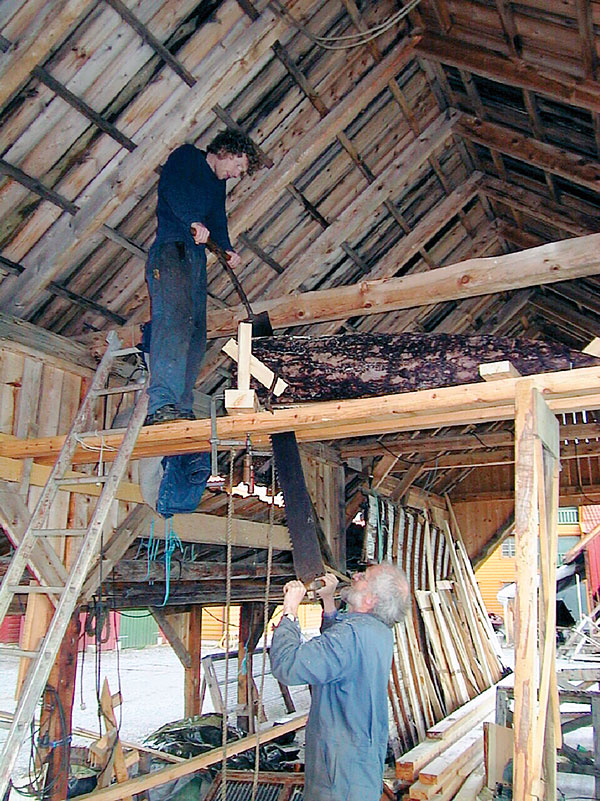

Some faerings are made for rowing, others for sail. This purpose is determined by hull shape, which in turn is a function of the shape of the halsar (singular, hals), or forward garboard planks. These are carved (never, in the authentic process, bent) into a winding curve—like a twisted sculpture—long before a boat is built. Indeed, a portion of the Fartøyvernsenter’s lumber-storage shed is dedicated to roughed-out blanks for these cherished pieces. Standing on end in rows and painted to slow moisture loss and prevent checking, they look like so many crude, white airplane propellers sharing space with additional piles of oak crooks set aside for sawn frames. When the time comes to refine these rough blanks, they will be laboriously pit-sawn into bookmatched pairs.

Other faering nuances: The stern is 3″ shallower than the bow; the hood-end nails are toothed like miniature harpoons for greater holding power in the oak stem; the top of the stem, with its delicate decorative beading, flares at its head, just so; the first of the boat’s three strakes is hung heart-side out, while the next two are heart-in. And then there is the Norwegian inch, an indigenous unit of measure (2.617 mm) used in faering construction. Peter Helland-Hansen, who explained all this to me in a private tour, has a folding rule—it looks like any other folding rule, at first—graduated in Norwegian inches. But he doesn’t need it for everything, because certain faering measurements need no such tools; the span, for example, is the spacing between the rivets, and it is the distance between the builder’s extended thumb and forefinger.

Courtesy Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter

Two builders use the long saw, or pit-type saw, to cut bookmatched, airplane-propeller-shaped garboards for a faering.

Two hundred hours of work go into a faering, said Helland-Hansen. “Probably it’s a little more. I would guess that’s the time an experienced builder would do it in…if he had no telephone. The square rivets are a sign of the old type,” he started to tell me, but then was interrupted by two eight-year-old boys who’d wandered from their parents, full of questions, and he turned his undivided attention to answering them. Not long after our conversation, a group of adults—Americans—entered the shop for a tour. Their eyes were adjusting to daylight, as they’d just emerged from the center’s cinema, having viewed a context-setting movie about Norwegian boats. The builder began his lecture again for them, without a trace of diminished enthusiasm. Helland-Hansen reckons he’s put 12,000 hours—six working years—into this boat type and its cousins. And that doesn’t include time spent talking to the Fartøyvernsenter’s waves of visitors.

The Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter sees 15,000 visitors per year. “Our main task,” said Gunnar Furre, “is to show people working. We are not trying to be a traditional museum.”

I was walking the waterfront with Gunnar, a ship preservation consultant working for the HFS, recalling the short stop I had made there a decade earlier during a whirlwind expedition on the fjord. Then, the place had a sleepy quality, with a small staff focused on the reconstruction of the galeas SVANHILD, a few buildings in need of paint, and interpretation cards here and there begging for visitors to read them. But the HFS then also had an undercurrent of youthful energy and, it seemed, big ambitions. It was no accident, I eventually learned, that I’d sensed shades of Mystic Seaport, for inspiration had been drawn from it and other institutions around the world.

I’d stayed for lunch then—talking boats and dreams and sharing food among the four or five employees. One of them was Geir Madsen, whose short-term post-college apprenticeship had by then stretched to eight years.

When I visited last June, I again stayed for lunch. The number of people attending the meal had grown tenfold. In a rumble of conversations, they flowed in from the various shops, gathering at noon in a second-story cafeteria at three long rows of tables spread with shared food—bread, cheese, meat, peppers, water, coffee. Midway through the daily feast, Geir rose to address the assembled staff and students. His comments, delivered in Norwegian, were met with three or four loud and vigorous bursts of applause. I’d meant to ask Geir what that was all about, but immediately after lunch he came over to me and said, “Excuse me, I’m late for a meeting.”

I was sitting with Gunnar, who shook his head, saying, “Meetings, meetings, meetings.”

“I don’t produce anything,” smiled Geir, as he bolted to keep pace with his administrative duties.

Courtesy Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter

Peter Helland Hansen (right) and Anders Geersten at work on a faering. Hull shape is determined by measuring from an overhead baseline, and using prop sticks to hold plank edges in place.

Gunnar picked up the thread. Geir’s announcements, he told me, were a welcome relief to staff and students alike, who weren’t sure whether they would have major projects to carry them through the next year or so. The office had received two phone calls earlier that morning confirming two big jobs, and I later learned that there was talk of a big new construction project—a replica. The new boat would be a copy of RESTAURATION, the first to carry immigrants from Norway to the United States. It’s a dream still, years from reality, but it fires the imaginations of the HFS staff.

Presently, Gunnar and I made our way to the ropewalk, staffed by Ingunn and Anja. They were at work on the finishing touches—“polishing”—of the boltrope that would reinforce the edge of a sail for “I don’t know…some Danish boat,” said Anja, her tarred hands running along tarred hemp. The strands must be twisted tightly for this application, she said, but the lay must be long so the sailmaker can open the rope for splicing.

Opposite the 82-meter-long ropewalk was a small display of fiber types, and a lesson. One of the fibers felt suspiciously synthetic—like a refined plastic—in the hand. Close inspection revealed that it was horsehair, favored 1,000 years ago for its ability to shed ice. “Viking Age nylon,” the interpretation card called it, quoting the Norwegian boatbuilder-scholar Jon Godal.

Gunnar and I next walked the waterfront. He described the large projects then underway: two fishing vessels, two elegant motoryachts, a hydrographic survey vessel, HANSTEEN, of 1866. “The philosophy of restoration,” he said, “used to be to bring the boat to its as-launched configuration. It is now, generally, to bring the boat to its last working configuration—though occasionally periods are mixed in the same restoration, in different areas of the boat.”

Courtesy Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter

Builders Aksel Bjelke (left) and Frode Saetre take a break from work on the motoryacht FAUN of 1916. She is to be relaunched this spring.

Documentation of restoration work—Gunnar’s forté—is meticulous. Each of the HFS’s jobs is recorded in words, drawings, and photographs, and bound in a book which is in turn shelved in the compact library of the documentation department. There are 35 such books lining these shelves at present—some covering various phases of the same restoration project. To date, the HFS has completed eight total restorations of large wooden vessels; the ninth, the motoryacht FAUN, is slated for completion this spring.

Ship restoration is paid for by owners, at an hourly rate. “We have a budget we should stay inside,” said Geir. The owners themselves do the fundraising for their projects, though the HFS will help with that, too. All money goes back into operating the Center—to wages for employees and small stipends for apprentices and trainees.

The annual budget for the HFS is 21 million kroner per year—about $3½ million U.S. One-fifth of that is financed by a quilt of Norwegian government agencies. “What’s left,” said Geir, “we have to earn.”

“All of these departments should be self-financing,” said Geir, quickly noting that they all aren’t. Ship restoration is, however, a major source of revenue, both of government grant money and fees paid by private owners. But Geir fears that “the thinking today is a little dangerous for us. They [the owners] want fixed prices…the cheapest way…. They don’t appreciate craftsmen.” Geir sees opportunity, though—in increasing the gate revenue, and in expanding even further the mission of the Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter.

A center for traditional maritime handcrafts is at the heart of the vision of the HFS’s future. It would, Geir said, be a school open to people who don’t have time for full immersion—people who would like a taste of various ship and boat building skills in one- or two-week courses. He also spoke of resurrecting on the HFS’s site a dormant boatbuilding school in Jondal, across the fjord. The curriculum of this revitalized school would include traditional as well as wood-composite construction; interior joinery; drawing, wood technology, and environmental- and health-related topics. For a while, that all seemed a dream, for discussion of moving Jondal’s school to Norheimsund stirred an ill political wind. But recent word has it that the revitalized school is to open in Norheimsund this fall, accepting students from around the world.

Courtesy Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter

Left—The Fartøyvernsenter’s ropemaker, Anja Hertsberg, in the center’s quarter-sized ropewalk. Right—A portion of the ropewalk’s interpretation shows the steps from loose fiber to spun rope.

The open-minded approach to the Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter’s mission makes a one-line statement of purpose something of a challenge. But, in a show-rather-than-tell way, the HFS simply exudes relevance. Perhaps that’s because the core job is to excite the imaginations of people young and old by putting the impassioned to work in front of visitors who care to observe—and in this way perhaps become impassioned themselves. Why is that important? It’s a reasonable question to ask, for in this age of quickening change, it’s tempting to discard old ideas and ways as a ball-and-chain on the leg of progress. But maybe seemingly archaic traditions hold us to something dear.

Courtesy Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter

The Center-owned Hardanger cutter VIKINGEN, built in 1915, carried refugees and supplies to the Shetland Islands in Norway’s World War II resistance movement.

Matthew P. Murphy

The bright future of Norwegian boatbuilding. Currently, 15,000 visitors come to the Fartøyvernsenter each year, where they not only watch craftsmen at work, but occasionally participate themselves.

This became especially apparent to me when I overheard one visiting woman’s wistful comment upon leaving the center-owned fishing boat VIKINGEN after an evening cruise of Hardangerfjord. The rugged little vessel—a powered “Hardanger cutter” with vestigial sailing rig—reportedly smuggled refugees and supplies to the Shetland Islands during World War II. She was restored at the HFS—relaunched in 1999 after almost a decade of restoration work there. Sounding like an iron heartbeat, the boat’s one-cylinder semidiesel engine requires no small measure of skill to run, and VIKINGEN herself has her handling quirks. Her captain had learned the magic touch; the boat seemed an extension of his hand.

“I could pay a lot of money to just hear that sound,” the disembarking woman said to no one. “It reminds me of my childhood.”

Matthew P. Murphy is editor of WoodenBoat.

This article originally appeared in WoodenBoat magazine No. 183 (March/April 2005)

The Hardanger Fartøyvernsenter, Box 53, N–5600 Norheimsund, Norway; tel. + 47 5655 3350; fax: + 47 5655 3351; info@fartoyvern.no; www.museumsnett.no/hfs/eng/