A Good Boat and a Day’s Work

Hauling traps aboard the fishing vessel RESOLUTE

Hauling traps aboard the fishing vessel RESOLUTE

Spray flies as RESOLUTE, a lobsterboat from Stonington, Maine, breaks a sea on her starboard side. “She’s unbelievably comfortable,” says her owner-operator, Ryan Larrabee. “You can’t beat the feel of a wooden boat.”

Although the vast majority of lobsterboats now built in Maine are fiberglass-hulled, there are still fishermen who appreciate the feel of a wooden boat under their boots. And there are builders who appreciate working with oak timbers and cedar planks. Peter Buxton of Stonington has built a couple of boats to his own design for a repeat customer—which is a statement in itself. Bass Harbor’s Richard Stanley has been building a hybrid combination of a wooden hull built to fit custom-molded fiberglass house and deck units for those who shy away from an all-wooden boat’s yearly maintenance. And then there is Peter Kass and John’s Bay Boat Company in South Bristol. Since opening for business in the fall of 1983, Peter (see WB No. 227) has remained true to his passion for wood, through both the good times and the lean times.

Early on, Kass boats were tagged as “Cadillac lobsterboats,” a description that turned out to be a bit of a cross to bear.

“The ‘Cadillac’ tag was well-intentioned,” Peter says, “but it might have scared some customers away, thinking we were high-priced. The fact is, we’ve always been competitive price-wise when you compare one of ours to a custom-finished fiberglass boat.”

A typical new-boat launching at Peter’s yard is like a family reunion: John’s Bay Boat owners usually turn out in force, showing their appreciation for Kass’s work (see related article, Building RESOLUTE). They know there’s more maintenance involved with a wooden boat, but to them it’s a small price to pay. Take 39-year-old Ryan Larrabee, for example, and his two-year-old 46′ John’s Bay–built RESOLUTE. He says it was the idea of owning a boat that was “hand-crafted for me and what I wanted—every inch of it—instead of having something that was popped out of a mold.”

Photographer Joel Woods spent an early April day with Ryan and his crew tending lobster gear aboard RESOLUTE and captured some of the highlights of a long workday. Put on your oilskins and come aboard for a day of tending traps in RESOLUTE.

In early spring, RESOLUTE typically leaves Stonington Harbor by 4 a.m. Ryan mans the helm from his captain’s chair at the inner steering station of the split wheelhouse. He checks in with fellow fishermen on the VHF as RESOLUTE heads off to haul traps set approximately 15 miles beyond Mount Desert Rock—which lies 21 miles off the Maine Coast.

Ryan is surrounded by an array of electronics that includes a color sounding machine, chartplotter, radar, and GPS. He laughs at the technology available these days: “The electronics we have now have made it easier than it used to be, for sure. Back in the day, lobstermen knew the bottom and could tell you all about where the shoals and deep holes were; now you have 3-D bottom machines that do it for you.

“I guess it’s a good thing, but at the same time…I don’t know. It’s different. It wasn’t that long ago that guys were running offshore just going by a compass course and marks off the land.”

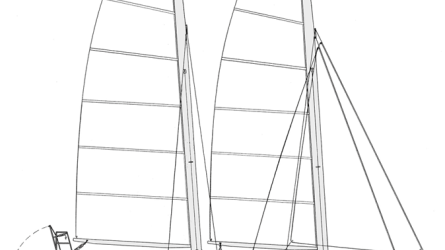

RESOLUTE was designed by her builder, Peter Kass, and measures 46′ LOA and 15′3″ across her beam. She draws 5′4″. Hull construction is 1¼″ cedar planking over 2½″ × 1½″ oak frames on 10″ centers.

In the early years of John’s Bay Boat, Peter worked with the late designer Carroll Lowell. It wasn’t until 1994, when the lobsterboat market began leaning toward beamier, bulkier hulls, that he drew up his own full-sized lobsterboat: a 41-footer for a Massachusetts customer.

“It was definitely what the market wanted at the time,” Peter said. “And we were definitely behind the trend compared to the fiberglass guys—but we went with it. Guys wanted bigger engines and wanted to still be able to shove them far forward. If we were going to build boats, it’s what we had to do. It seemed to work.”

The lobsterboats built in the past few years have added another feature to the equation: larger belowdeck tanks to hold the catch. For a lobsterman, this translates to income; for a designer and builder, this means extra weight to contend with.

RESOLUTE’s 803-hp C18 Caterpillar diesel engine, fitted with a 2.5:1 reduction gear, spins a 36″ × 42″ four-blade propeller, pushing the boat along at a top speed of 23 knots—with an easy 17.5-knot cruise.

Ryan stands at the helm of RESOLUTE’s outer steering station, approaching an end buoy. The lobster gear he and his two-man crew will be hauling on this particular day is rigged as 15-trap trawls with a marker buoy at each end. The control for the 14″ hydraulic hauler is mounted on the bulkhead at Ryan’s fingertips; the screens of the electronic equipment inside the wheelhouse are visible from where he’s standing.

These traps have been set on bottom that runs from 500′ to 600′ deep, as that’s where the lobsters seem to be at this point. In a few days—or a few weeks—the population may have moved, and there’s no guarantee they will be in this same depth of water a year from now. Veteran lobstermen will tell you there are signs to watch for, trends to follow, and cycles within every season. And there are no guarantees. In the words of one longtime fisherman: “I spent 80 years tryin’ to figger out lobsters and never did. I guess that’s why I done all right at it.”

Sternman Joe Sullivan leans out over RESOLUTE’s rail to gaff a buoy as Ryan throttles the big Cat back and reaches for the trap-hauler control handle. Thus begins a flow of work that, when performed correctly, is as well-choreographed as a dance routine (although you probably wouldn’t want to say that to the parties involved).

The rigging plays a factor, of course: Match the height of the davit block and the length of the rope beckets on the traps properly, and it will make breaking the gear in over the rail much easier.

And then you have the men themselves. The old adage is, “If you find yourself doing nothing, then you must not be paying attention.” A good man working the rail with the skipper is always mindful of the next trap coming up—and the next trap, and the next. And the man aft of him is also aware of the window of time they have to pick and bait a trap and move it aft before the next one is hauled aboard.

At the same time, every lobster trap is scanned for any chafed meshes in the twine heads or broken wire in the outer cage that needs to be repaired before re-setting it. A hole in a lobster trap is a hole in the wallet.

Sullivan and fellow crewman Keali’i Mano pick a trap clean on RESOLUTE’s rail. (And in case you’re wondering, no, Keali’i is not a typical Downeast name. He moved to Maine from Hawaii.) In the foreground, you can just see bait needles loaded with rockfish, which was trucked in, frozen, from the West Coast, that will be used for this day’s trawls. Rockfish is typical of what some lobstermen call “hard bait”: bigger fish that have been filleted, leaving a body with enough meat attached to last longer in traps set in the deeper water.

During the warmer months when lobsters tend to head for shallower depths to shed, herring will be the bait flavor of choice, stuffed into mesh bait bags. The herring typically doesn’t last as long, but traps are also hauled on a tighter schedule with shorter sets.

On the outboard edge of the bait box is a tray of lobster bands, waiting to be slipped over the claws. These rubber bands became the norm in the 1970s, replacing whittled softwood plugs that used to be stuck into the soft membrane of the claw’s “thumb” to prevent it from opening.

Joe sends a “snapper”—an undersize lobster—back overboard. With a bronze measure in one hand as he picks the trap, Joe ensures that all “keepers” meet the minimum (and maximum) carapace lengths required by Maine law. In the meantime, Ryan eases RESOLUTE’s transmission in and out of gear, staying up on the groundline as the hauler winds in the trawl.

Barring any snarls in the gear, the ideal situation is to have the rope leading out away from the hull and angled just slightly ahead; each trap will trail slightly aft of the groundline as it breaks the water and rises toward the davit.

If the man on the rail can time his grab properly, he can make use of the trap’s upward momentum as he swings it aboard. It isn’t always a matter of muscle when it comes to handling lobster traps; rather, it’s a feel for the constant motion of the boat and gear and using it to your advantage, rather than fighting against it.

Keali’i launches a trap over the side. As with everything else, there’s an art to re-setting lobster gear: sloppiness can cost you money. A trap that lands upside-down will not fish properly. Lobstermen use various combinations of weight and runners (the skids on the bottoms of the traps) to help ensure they’ll sink right-side up, but the man on the rail is the key to success.

At the same time, the man back aft needs to be conscious of the rope down by his feet—and with a 15-trap trawl, there’s plenty of it. RESOLUTE is a steady workboat and Ryan a skilled captain who is always mindful of what’s going on around him. But things can happen quickly on the water, and there aren’t a lot of second chances.

Most lobstermen wear a sheathed knife that’s easily accessible in an emergency. Old-timers often insisted on having a sharply honed knife jammed up under the rail in the aft corner of the boat’s hauling side—the “last stop” if a man had a turn of warp around his boot and was headed over the side. “You could do that with a wooden boat,” says one veteran. “You can’t stick a knife into one of them plastic boats.”

Keali’i works his way down the starboard rail, setting a trawl back.

Vinyl-coated wire lobster traps first arrived on the scene in the 1970s to challenge the traditional wooden ones. You might wonder if a lobsterman with a wooden-boat soul wouldn’t prefer to fish wooden traps, but the sad fact of the matter is, there just aren’t any sawmills cutting trap stock these days. Most wire traps are built with enough custom touches to satisfy the average fisherman’s need to make his gear his own.

Take the color combinations of trap wire and heads (the twine, funnel-shaped entrances in the sides and interior) that are available, for instance: Whereas early wire traps of the 1970s and ‘80s were usually either black or dark green, today’s are available in a wild rainbow of colors that includes bright yellows and blues—with twine heads that sometimes clash in the most garish of ways.

Some lobstermen will tell you that their particular combination of colors is the only one that will really fish, although their neighbors seem to be doing just fine with their own blend of colors. Others admit they simply like their gear to “look a little different.”

There are fiberglass lobsterboats these days built in the same 46′ range as RESOLUTE that are 2′ (or more) wider, but for the boats he builds, Peter seems to have found a nice combination of above-deck workroom and below-deck spaciousness in a hull that has a certain sleekness about it. One of the advantages of wood, of course, is the ability to tweak a design to fit a given customer’s needs: Three boats in a row may have been birthed from the same basic design, but they might all be a little different.

OUTER FALL was the next lobsterboat built by John’s Bay after RESOLUTE, and though she shared the same bloodlines, she was just a tad wider (15′6″) and longer (47′). OUTER FALL’s owner, Jim Tripp, told Peter he wanted something “a little bigger than, a little faster than, and just as comfortable as” the 42-footer the shop had built him in 1996. Kass jokes that Tripp just wanted to be able to say, “He’s got the biggest John’s Bay boat.”

RESOLUTE is back at the dock, 12 hours or so after she left. Ryan and his crew have hauled 400 traps—half of the total he’s allowed to fish by Maine law.

While some of his peers choose to stay out overnight and haul all their gear, Larrabee says he’d rather “put in a long day and sleep in my own bed at night, even if it costs a little more to do it.” And there you have a facet of lobstering that is as old as the fishery itself: the balance between spending time out on the water to support the family and spending time with the family. It’s a tough juggle at times, where shoreside occasions need to take a back seat to a profitable run of lobsters, or traps that need to be shifted before an impending storm.

Some lobstermen and their families master it; some struggle with the balance all their lives. There’s nothing easy about this work. But it helps to have a good boat under your boots. Ask Ryan, and he’ll tell you he does, for sure.

Joel Woods is a commercial fisherman who has worked in a number of fisheries along the East Coast. During his many years of fishing, he has learned to photograph the raw beauty and power of the sea.

Brian Robbins, a former offshore lobsterman, is senior contributing editor for Commercial Fisheries News. He lives in the midcoast Maine region with his wife, Felicity.