The Boat as Emblem

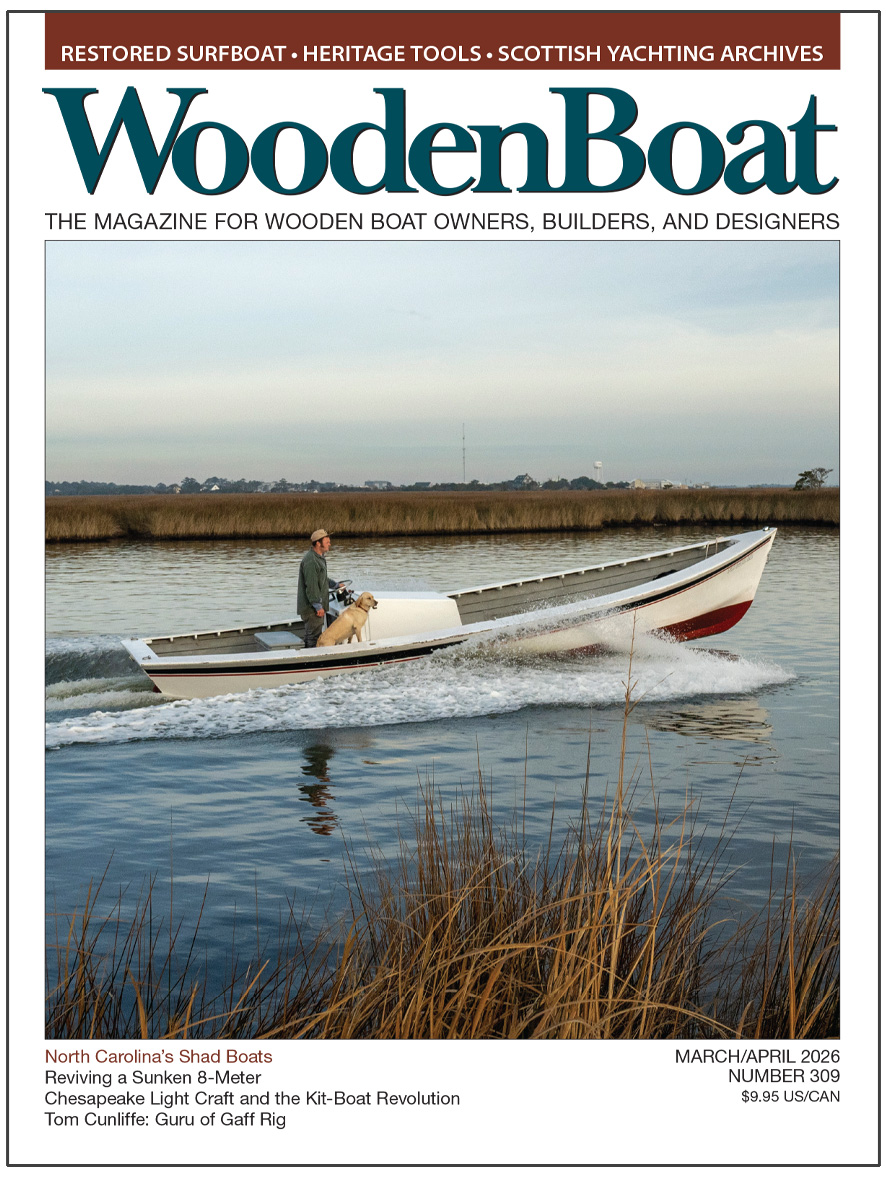

In his article beginning on page 56, Paul Molyneaux observes that the North Carolina shad boat is a reflection of its region’s history. Indeed, as Paul details in his article, shad-boat construction, which began in the 1870s, was adapted to available resources, and hull forms morphed through the switch from sail to power and the evolution of the fishery. While the modern shad-boat emerged after the Civil War, its design is rooted in a millennia-old hull form, carved from big logs by the native Croatoan people of the Outer Banks. The boat’s regional symbolism is so powerful that the North Carolina General Assembly designated it the Official State Historic Boat in 1987.

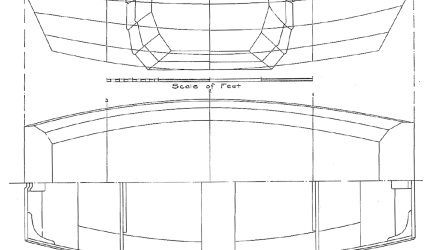

Jan Adkins, in his installment of Skills 101 beginning on page 37, notes, “The goal, purpose, time, and circumstance of a boat shapes its design.” In the case of the shad boat, it’s remarkable that the goals and circumstances that shaped it could have held on for so long. But it’s not unique. My thoughts turn to Scandinavia when I think of boats as cultural emblems—of hull forms and construction concepts that held on through centuries, shaped by environment and need. The Nordic lapstrake, or “clinker,” tradition is so powerful a cultural emblem—and so endangered by changing times—that in 2021 it was added to UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, to ensure its preservation. Boats built in this tradition range from Viking-era watercraft to the faerings that roamed Norway’s fjords to modern-day fjord cruisers, built of fiberglass but with molded “strakes” to mimic ancient planking techniques. The influences of lapstrake-planked Viking-era boats are still visible all over Scandinavia and have even found a place in modern recreational kit boats built of plywood. We see this in several of John Harris’s designs beginning on page 86.

Indeed, Harris has tapped many traditions in his designs, and his workboat-derived concepts have found an audience in the recreational realm. His Lighthouse Tender Peapod, for example, is based on the peapods of the Maine Coast—double-ended multipurpose workboats once used for hand-hauling lobster traps along bold, rocky shores. John’s Southwester and Northeaster Dories are rooted in a Massachusetts tradition of beach-launched fishing boats that transitioned, as early as the late 19th century, into recreational racing craft. His Pacific Proa is a wood-and-epoxy interpretation of Oceanic voyaging craft. John’s company, Chesapeake Light Craft, has many kayak designs; in fact, it was founded on this most ancient and emblematic watercraft of the Arctic.

“The changes [the shad boat] has gone through in design, power, and function,” Paul Molyneaux writes, “perfectly mirror a unique slice of Americana.” Likewise, Nordic clinker craft, Maine peapods, Massachusetts dories, Oceanic proas, and Aleut and Greenland kayaks are all rooted in regional traditions that are hundreds—even thousands—of years old. They have evolved over time. They are reflections of customs, traditions, struggles, and values, and have found new agency and appreciators. Regional watercraft survive because they fit a place and a purpose. If you’re reading this, or have built, sailed, or enjoyed these boats, then you are part of that purpose.

Editor of WoodenBoat Magazine