Sakonnet One Designs

The community built around a beloved fleet

The community built around a beloved fleet

PETER GOLDBERG

When John Alden designed these heavy, capable daysailers, he might not have dreamed that the community of sailors in Rhode Island’s Sakonnet Harbor would come to care for them so faithfully and for so long. A culture has been built around them, cemented by the fun of afternoon racing and the chores of yearly maintenance.

Sakonnet Harbor lies at the tip of a quiet Rhode Island peninsula that juts into the Atlantic Ocean. It shelters a commercial fishing operation on one side and a small, busy yacht club on the other. The clubhouse is so tiny that it could easily be mistaken for an equipment shed, but it has freshly painted, white window boxes bursting with red geraniums and a jaunty burgee flying from a flagstaff carved to resemble a goose’s head. Adults and children head in and out of its open doors in an almost constant stream. Up and down the long pier they go, carrying sailing and fishing gear of all varieties, calling to one another, launching small sailboats, and rowing dinghies to boats on moorings that dot the harbor.

MARA LOZIER SHORE

The author and her father, Peter Lozier, are grinning during a 2017 race despite needing their foul weather gear.

This colorful, picturesque place is home to eleven 18′6″ wooden John Alden–designed daysailers called Sakonnet One Designs. Members of the Sakonnet Yacht Club here have sailed, raced, repaired, and maintained these boats since the design’s debut in 1938. Remarkably, all but one of the existing boats of this design—the exception being the oldest, which is in the Mystic Seaport Museum—still sail from Sakonnet.

What accounts for this longevity? They are not the easiest boats to sail, nor are they the most economical to maintain. But they are beautiful, elegant, and perfectly suited to this place, and they are owned and sailed by a community of stubborn, self-reliant traditionalists. To area residents, they are talismans.

The Sakonnet Yacht Club was founded the same year these sloops were designed. Alden himself was a summer resident here, and he conceived the boat for the prevailing conditions of Sakonnet: wind and waves. The southwest breeze that builds almost every summer afternoon, combined with a fetch that reaches right across the Atlantic, means that there is almost always wind, swell, and chop. Conditions in Sakonnet are usually slightly challenging, and frequently quite challenging.

The boats were originally built at the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. in 1938–39, but hurricanes decimated the nascent fleet. Then in 1954, Hurricane Carol wiped out 10 of the boats, along with the pier and the clubhouse. The only exception was TAUTOG, deliberately scuttled in advance of the storm by its owner and skipper, Elizabeth Dawson. She was a force to be reckoned with—young, strong, and a fast sailor. TAUTOG was her pride and joy, and she routinely beat the overwhelmingly male skippers of the fleet, often with an all-female crew. TAUTOG is the sole survivor of the pre-1954 fleet, and is currently a part of the collection at Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, Connecticut.

In 1954–55, after Hurricane Carol wrecked the entire fleet save the Dawson boat, Harry Towne, a former employee of the then-defunct HMCo., built 10 new Sakonnet One Designs on the Herreshoff property in Bristol. His own yard in nearby Tiverton had been destroyed in the hurricane. All of the now-existing boats, except Dawson’s, are from this batch that Towne built in 1954–55. They are mahogany-planked, just like the 1939 boats.

DALE WALKER

CHIQUITA, followed by ELISHA and CUTTY WOW, on a typical summer day of lively racing.

Sakonnet One Designs are stiff, beamy, and comfortable, with high freeboard and a coaming to help keep sailors dry. They have solid spruce masts and deep, cast-iron keels. They carry a large mainsail; a small jib; and a symmetrical spinnaker, as Alden specified in his original sail plan.

The boats are sailed and raced hard, often with the leeward deck awash. They typically have a crew of three, although two or four is not uncommon. They can be singlehanded, but need more crew to fly the spinnaker. Most of the boats have been owned by the same families for generations, and racing crews stay together for decades. Several of the boats have had only one or two sets of owners in their 64-year lifespan. And, for the most part, the boats are maintained by the people who sail them, inside local barns and boatsheds.

The month of May is a busy one in Sakonnet. Like everywhere in New England, as the ground thaws and the land becomes green again, people come out of hibernation and begin planting, pruning, painting house trim, repairing lost shingles, and otherwise getting ready for summer. For Sakonnet One Design sailors, the most important of these spring rituals is opening the boatsheds and getting the boats ready for the water.

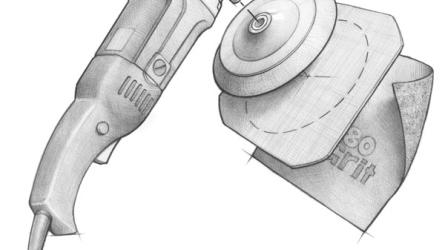

There are hulls to scrape, sand, and paint; decking and rigging to be repaired; sails to mend; spars and brightwork to varnish; and tweaks to last year’s setup to be made. Notes are taken, family conferences held (“Can we get away with this rigging, floor timber, decking, and keep on sailing for one more year, or do we need to replace it?”), and the work begins.

MARA LOZIER SHORE

Ben Shore, the author’s son, who was 11 years old when this was taken in 2011, chips in along with the rest of the family during maintenance season. Here he’s sanding the cockpit bench tops of his family’s boat.

When the spring outfitting is complete, the boats are towed down to the old hoist, using trailers of varying age, ancestry, and roadworthiness. The boats are then strapped to the hoist, plucked up off their trailers, and set into the sea.

Certain sailors, myself included, have been known to spend the first night or two on their boats, pumping every few hours until they’ve swollen tight. On rare occasions, boats must be hauled out again and their leaks fixed. One June in the late 1970s, my father and my uncle launched their boat, patted each other on the back, and went to dinner. The next morning, they met down at the club expecting to finish rigging and get set up for the first races. They rowed toward their mooring, but their boat was not there. Not even the mooring ball showed. They looked all around, and, finally, looked down. Twenty feet under water, the white deck of their boat gleamed from its resting place.

Mostly, though, preparation pays off and launching goes smoothly. After the shakedown sails, kinks are worked out and the boats start to hum along “in the groove.” Picnic sails are organized, practices run, and the Saturday races begin. Racing takes place every Saturday afternoon during the summer, and they can get in several races before retiring to the clubhouse to relive the highs (and lows) of that day’s competition.

A few times each summer, the boats participate in pirate races, raucous games in which all the boats must stay inside the buoys while the “pirate” boat launches tennis balls into as many cockpits as possible. If a ball lands in your boat, you then become a pirate, and your job is to lob tennis balls into other boats. Tennis racquets, lacrosse sticks, garbage can lids, and fishing nets are all encouraged to help both fend off and to gather ammunition. Dinghies are boarded and capsized by marauding pirates, and more than a few sailors end up in the water. It is a noisy morning of hilarious fun for all ages. During the event, Sakonnet One Designs tend to be sailed by parents or grandparents and filled to the gunwales with the very youngest and most timid sailors who have so much fun that they forget they are sailing. The big, open cockpit and high freeboard make everyone feel secure, although it is an easy target for a well-aimed tennis ball.

PETER GOLDBERG

Geoff Taylor adjusts the spinnaker pole aboard CUTTY WOW as AUGUSTA (light blue spinnaker) follows. This is from August 18, 2013, and it was a light wind day. The author says, “Sakonnet One Design spinnakers are reasonable to set, douse, and jibe.”

The pirate races exemplify what gives Sakonnet One Designs their staying power: They are sturdy and seakindly, and perfectly adapted to the prevailing local conditions, even when raced by sailors of differing ages and abilities. They promote community because they are sailed, maintained, and repaired by generations of local sailors who pass on their know-how and strategies as new sailors join their ranks. Several of the boats, mine included, are regularly raced by three generations of the same family.

Sakonnet One Designs can often be seen heading out of the harbor in the late afternoon for a sunset cruise. Stories abound of epic adventures to Cuttyhunk and Block Island. My family also uses our boat for camp-cruising. Every summer, since my children were tiny, we have loaded aboard a picnic basket and sleeping bags, a lantern to hang from the boom, and our books and sketchbooks. We rig a boom tent to keep us dry and then snuggle in, with nothing to do but enjoy each other and watch the stars (or the occasional storm). Our children are now mostly grown, but still they cherish this summer ritual; it is one of our fondest memories of their childhoods.

If you happen to be down at the end of that quiet peninsula on a summer Saturday afternoon, you can watch the colorful fleet from the end of the town breakwater as the sailors jockey for position on the starting line, or as the boats march downwind with their chutes flying. It is a gorgeous sight. And if you happen to be in Sakonnet on a spring afternoon, you may find those same people busily sanding, caulking, or painting their boats. They will be happy to share their love of the Sakonnet One Design with you.

Mara Lozier Shore is a writer, attorney, and environmental advocate. She lives in Greenwich, Connecticut, and Little Compton, Rhode Island, with her husband and three children. Mara is a former Commodore of the Sakonnet Yacht Club and is Fleet Captain of the Sakonnet One Design fleet. She is writing a book on the class that will be published in 2019.