September / October 2020

TUGZILLA

Aesthetically, functionally, and conceptually, TUGZILLA is pure tugboat. With a boatbuilding future clouded by the coronavirus pandemic and its economic fallout, designer and boatbuilder Sam Devlin is using her to launch a sideline towing business in southern Puget Sound. Right—Shift and throttle controls are separate, which Devlin says works best for intricate maneuvering.

Sam Devlin’s boat-design catalog is awash in tugboats—cute little pretend tugs, honest-to-God working tugs, and imposing motor cruisers whose profiles hint strongly of ancestral tug DNA. Although 95 percent of his boatbuilding business in Olympia, Washington, over the past 43 years has involved pleasure boats, it’s clear that tugs are somehow lodged in his heart and his inner eye. He swears, in fact, that when he was five years old, he won a kindergarten art competition with a drawing of a tugboat. And he says his vision of a life building boats first occurred while working aboard a wooden tug in Alaska during his college years.

“I’ve had this theory for a long time that there’s an innate wiring that happens with people,” Devlin muses. “We have boat shapes, or caricatures of them, lodged in our minds based on what we grew up seeing. Northeast people are always seeing lobsterboats. Catboat people look at all boats through catboat eyes. The kind of boats I like best are the fishing boats and tugs I grew up seeing on the Northwest coast. I think the closer I keep a design shape to these simple caricatures, the more visceral approval it gets.”

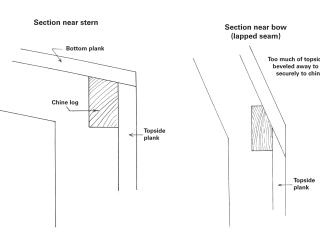

Among the tugs in Devlin’s stable of stitch-and-glue designs, available either as plans for amateur builders or custom-built boats from his shop, is the 25' 10" TUGZILLA. It’s a real, no-nonsense working tug, though its trajectory from CAD drawings to the first finished iteration, featured here, has been a spasmodic zigzag 10 years long.

To read the rest of this article:

Click the button below to log into your Digital Issue Access account.

No digital access? Subscribe or upgrade to a WoodenBoat Digital Subscription and finish reading this article as well as every article we have published for the past 50-years.

ACCESS TO EXPERIENCE

Subscribe Today

1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION (6 ISSUES)

PLUS ACCESS TO MORE THAN 300 DIGITAL BACK ISSUES

DIGITAL $29.00

PRINT+DIGITAL $42.95

Subscribe

To read articles from previous issues, you can purchase the issue at The WoodenBoat Store link below.

Purchase this issue from

Purchase this issue from